Part 72: The Isolated City

Chapter 8 - The Isolated City - March 1831 to January 1833In many ways, 1831 was the year that would finally decide the outcome of the Tirruni Wars. The convenience of retrospect cannot be underestimated, of course, but this was the year that bore witness to the Andalusi invasion of Morocco - a feat that many had considered hopeless folly, if not downright impossible. But somehow, an army was landed off the coast of Rabat. That army then besieged Tangier, and despite suffering countless sorties and disease outbreaks over the next year, they eventually captured the city. That victory was quickly followed up by another, as the Andalusi launched a bloody assault of Ceuta, seizing the fortress after a lengthy battle in the streets.

Once the northern coast was secured, the Andalusi began to push south, and at that point it couldn’t be denied any longer - the Almoravids were in big trouble.

March of 1831 thus began with the Majlisi Guard laying siege to Fes, the economic capital of the Almoravid Empire. The massive city was quickly surrounded and blockaded, but North Africa wasn’t the only theatre of war, and the Berbers were fighting battles all across the Mediterranean.

In the east, the Moroccans had launched an invasion of the Levant, capturing dozens of coastal towns and fortresses in a sudden offensive. They then pushed inland, crushing an Egyptian army before besieging and capturing Jerusalem, opening the road into Egypt itself.

The Egyptians, meanwhile, were also embroiled in another conflict further north. Dominance over the Levant had been contested between the Apanoub and Vakhtani dynasties for centuries now, but their latest war had gradually spread to a myriad of neighbouring countries, including Bulgaria and the Vali Emirate.

And unfortunately for the Armenians, who were surrounded by enemies on all fronts, the war was not going in their favour. Large parts of Anatolia had already been lost to the Egyptian-Kurdish alliance, but the fighting has since settled into a stalemate, with the Egyptians distracted by the Berber invasion and the Kurds too weak to attack alone.

This short respite on the southern front gave the Armenians enough time to deal with the western threat, decisively crushing the Revolutionary Serbian army in the battle of Smyrna. Once the Armenians had recaptured the Aegean coastline, the two powers sent emissaries to begin negotiations, with a peace treaty finally announced in the summer of 1831.

Revolutionary Serbia, it seems, was gradually being torn apart from the inside out. The white peace with the Vakhtani Caliphate had demolished the prestige of the Republic, and proved to be the catalyst for the outbreak of countless revolts and rebellions all across the Balkans, ranging from separatist insurgents to monarchist rioters.

And in a foolish attempt to unite the people behind them, the revolutionaries decided to declare war on the tiny kingdom of Greece, anticipating an easy victory.

But the Greek army, however small it may be, was a unified force hardened by their constant struggle with the Moroccans. They were able to defeat the undisciplined peasant armies of Serbia, surrounding and crushing them in the Pindus Mountains, before launching an invasion into Serbian territory.

And with large parts of the Balkans quickly falling to rebels and invaders, it would seem as though the days of the Republic were numbered.

Further north, meanwhile, the recently-proclaimed Russian Empire had just finished up a short campaign against the Principality of Cherson. The principality’s Romanian lands were puppeted by the Russians, securing their influence north of the Danube.

The eternal rivals of Smolensk, meanwhile, had political machinations of their own. Tsar Vasiliy VII, humiliated and jealous, decided to counter the proclamation of Russia by crowning himself the first Emperor of Scandinavia, though he refused to abandon his claims to Novgorod and his eastern territories.

And in an effort to centralise his new empire (and buy the loyalties of his vassals), Tsar Vasiliy reshuffled his imperial cabinet, replacing a number of Russian advisors with Swedes and Norwegians. Several of these deposed Russian magnates would eventually return east, where they set up a new government in the vast, barren lands of Siberia, which had slipped from Novgorodian control.

Tsar Vasiliy, meanwhile, was determined to repair his image on the world stage. So as 1831 drew to a close, he declared war on the German principality of Hamburg, hoping to score an easy victory and secure control a foothold in the Jutland peninsula.

Unfortunately for him, the Tsar didn’t anticipate the intervention of Hannover, the self-proclaimed protector of German states. King August-Wilhelm thus pulled his armies from the war in the south, leading them on a forced march into Hamburg, where they clashed with the newly-raised Scandinavian troops in a series of bloody, one-sided battles.

For the Duke of Bavaria, this was enough for him to pull out of the Tirruni Wars entirely. The fortunes of Bavaria had greatly declined since its glory days under the Republic, and with the monarchy still very frail, the Archduchy had no hope of prevailing over Tirruni - not without Hannover.

What the Bavarians lacked in daring, however, the Hungarians more than made up for in manpower and zeal. January of 1832 saw the Hungarians launch another massive offensive into Italy, and with Tirruni wintering his armies north of the Alps, there was nothing to stop them from flooding into the peninsula unopposed.

Whilst Tirruni was busy juggling crises, the early days of 1832 saw the Andalusi score another important victory, with the reinforced walls of Qartayannat finally breached and overwhelmed.

Even with the walls of the fortress blown apart, however, the battle was only just beginning. A massive Berber-Indian force was garrisoned in Qartayannat, so a gruelling, bloody battle in the streets quickly followed.

The siege of Qartayannat, fortunately, had sapped the defending force of its morale and supplies, so the battle ended in a crushing Andalusi victory. Day’s end saw the city littered with lifeless Berbers and Indians, with the total enemy casualties numbering over thirty thousand - six times more than what the Andalusi had suffered.

Bad news trickled into the city within a few days, however, souring the celebrations. Apparently, Almoravid reinforcements had landed a few miles south of Qartayannat, and had resorted to burning and pillaging the countryside.

Grand Vizier Zulfiqar, who was leading the army from afar, immediately sent them south to confront the Berbers.

And despite being pushed back in the early hours of the battle, a series of tactical withdrawals and well-timed reinforcements proved enough to seize another huge victory, with large parts of the Moroccan army surrounded and crushed just as dusk broke.

Once the recaptured fortresses were garrisoned, Zulfiqar felt secure enough to pull back again, making Qurtubah his base of operations. At just 20000 soldiers, the army was still quite small, but without the funds to begin new recruitment programs, the Grand Vizier was forced to make do with simply streamlining the reinforcement process.

The attention of the Grand Vizier then slid south, where Sheikh Fadhil al-Farihi had led the Majlisi Guard from one glorious victory to the next, accumulating unfathomable amounts of prestige as he did so. And as the summer of 1832 crept closer, he added to his fame with another monumental triumph - the capture of Fes.

Despite its importance as the largest, richest and most populous city in Morocco proper, it took only six weeks for the Majlisi Guard to capture Fes, dealing an immense blow to the perceived invulnerability of the Almoravids.

And with Fes now in their hands, the road to Marrakesh itself stood open. Sheikh Fadhil pushed south with speed, determined to lay siege to the isolated city. As he did so, however, his scouts brought him news of a vast construction project along the Moroccan coasts, where the Berbers were franticly expanding their naval prowess.

The glory and prestige of capturing the capital of the Almoravid Empire proved far more tantalising than raiding sparse coastal cities, however, and Sheikh Fadhil decided to press on with his campaign.

He did send word of the naval expansion to the Majlis al-Shura, however. But even when armed with the knowledge, the assembly could do little to counteract it - they were receiving no subsidies, the budget was in the red and cash reserves were already being stretched thin, so there was no hope of further expanding their own navy. The Andalusi would have to make do with what they already had.

At the moment, anyways, the Majlisi Fleet was holding its own just fine. In fact, under the command of Grand Admiral Sayf al-Talasi, 1832 saw the navy notch a number of impressive victories in the Gulf of Qadis, ensuring that the straits remained Andalusi for the time being.

As the summer drew to a close, however, another Berber army began to gather around Tangier. Largely drawn from native Berber tribes, the small army besieged the fortress late in July, hoping to seize it before the Andalusi could intervene.

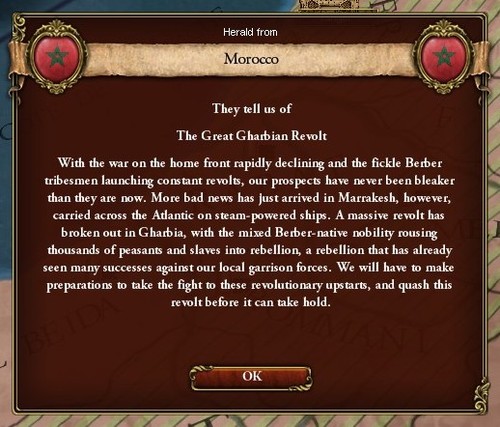

Unfortunately for the Almoravids, however, their problems would only multiply over the next few weeks. August brought news from the vast western continents with it, where harsh taxes and relentless conscription had finally incited the local Berber nobility to rise up in revolt, a revolt which quickly escalated into a continent-wide revolution.

Later called the Great Gharbian Revolt, this revolution would see the birth of the first self-governing Berber states in the new world, though their independence hinges on how the war in the old world progresses.

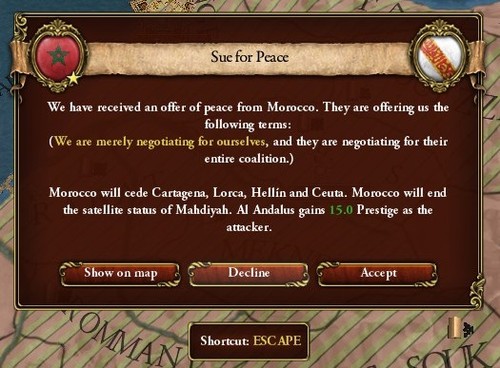

Becoming more desperate with every passing day, the Almoravid Sultan Yahya was forced to acknowledge that some battles could not be won, and offered to surrender Qartayannat and Ceuta to al-Andalus in return for peace.

That was not enough, however. The Majlis wanted nothing less than complete control over the Straits, and with Marrakesh at their mercy, they were not inclined to make peace just yet.

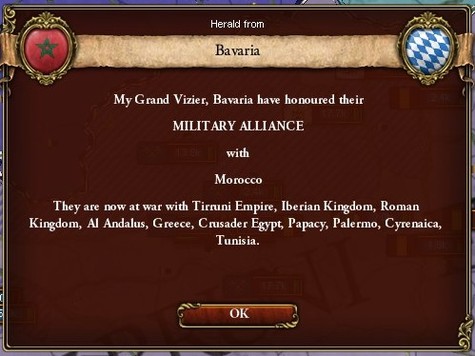

The Almoravids scored a minor victory late in August, with Berber diplomats convincing the Archduke of Bavaria to rejoin the struggle for Italy, his pockets laden with bribes and heavy with promises.

As was usual, however, the Bavarians chose the wrong moment to enter the fray. Sahim Tirruni had spent the past few months raising several new armies, largely drawn from his Occitan territories, and now felt confident enough to launch a counter-attack into Italy.

Always eager to show off his tactical prowess, it didn’t take long for the Emperor to shift the odds back in his favour, with the Hungarians pushed back and the Bavarians crushed within the span of weeks.

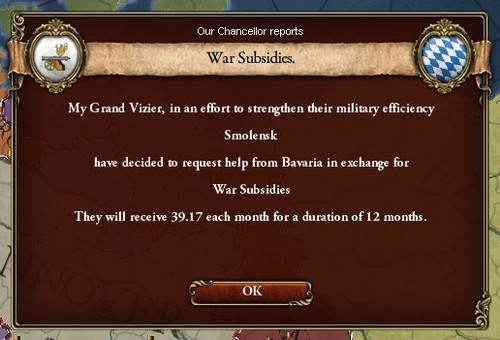

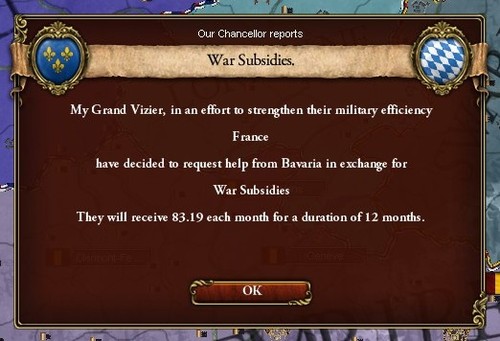

And with tens of thousands of soldiers gathering in north Italy, both Russia and France began to grow nervous at the prospect of further aggression. Determined to keep Tirruni contained, both powers began to flex their own muscles, agreeing to provide Bavaria with massive subsidies in return for them staying in the war.

Needless to say, the situation was looking increasingly bleak for the Almoravids. Desperate to keep Tirruni distracted whilst they dealt with the Andalusi, the Berbers began to negotiate with surrounding European states, though they were largely met with hostility and antagonism.

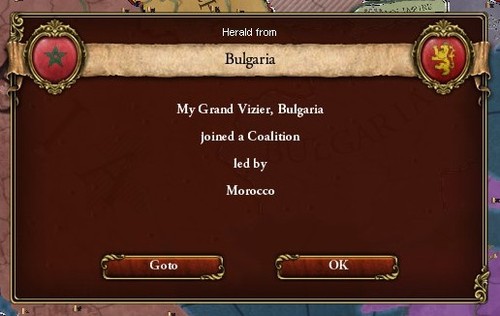

The first few months of these talks thus bore little fruit, with only the Tsar of Bulgaria agreeing to pledge some of his own forces to the war on Tirruni.

At the same time, the Almoravid navy landed a decently-sized army near Napoli, numbering almost 30000 soldiers. Before they could do much damage, however, they were met with three different armies, all led by Emperor Tirruni himself.

And with superior numbers and tactics on his side, the battle could only end in one way, with the Berber force surrounded and wiped out in the mountains of central Italy.

Shifting back to Iberia, however, the Almoravids had concurrently launched another invasion of the peninsula. The 20000-strong army landed at Shlib and immediately pushed north, capturing Batalyaws before being pinned down by Zulfiqar, who was determined to crush the invasion before it could escalate.

Armed with his knowledge of the local terrain, and backed by another reinforcing army, the battle ended in another stunning victory for the Andalusi. The Berber force was almost entirely wiped out, with only a few hundred escaping the battlefield alive, before being hunted down over the following weeks.

The tiny Moroccan garrison in Batalyaws surrendered upon hearing of the massacre, and were rewarded with their lives, with the soldiers escorted south and onto Almoravid ships.

Further south, meanwhile, the force besieging Tangier had continued to grow over the past few months. Recent Andalusi successes had apparently galvanised the Berber tribesmen, who supplied the manpower for this new army, determined to throw back the invaders.

And after almost a year of siege, blockaded on both land and sea, the Andalusi garrison finally succumbed the besiegers. Tangier was lost, and with it Andalusi dominance over the straits was broken.

It didn’t take long for word of this disaster to reach Sheikh Fadhil, of course, but the noble-born commander refused to abandon his siege of Marrakesh. Andalusi artillery had finally breached the city’s fortifications, and with battle breaking out all around the Almoravid capital, the sheikh was closer than ever to securing his ambitions.

At the same time, half a continent away, the Scandinavian-German War had turned firmly against the aggressors. After seeing some success in Denmark, Hanoverian armies rallied and pushed the the invaders back, before launching a counter-invasion into Scandinavia itself.

German armies marched across the peninsula with ease, burning and pillaging as they did so, and had pushed north of Fredrikstad before the Scandinavians conceded defeat. The subsequent peace treaty saw ‘Emperor’ Vasiliy humiliated yet again, whilst Hannover’s influence in north Germany was solidified, only furthering the daunting ambitions of King August-Wilhelm.

The king had much more immediate worries to deal with just then, however, as word reached Hannover of a sudden offensive into Bavaria. Utilising forced marches and ingenious tactics, Tirruni was able to crush the Bavarian army in a series of battles, pushing northward as he did so. By the end of 1832, large parts of Bavaria were occupied by Tirruni troops, with München itself brought under siege before the end of December.

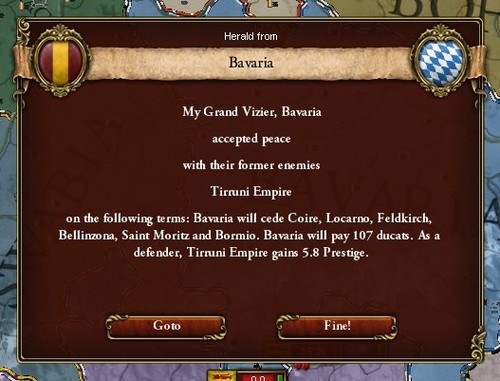

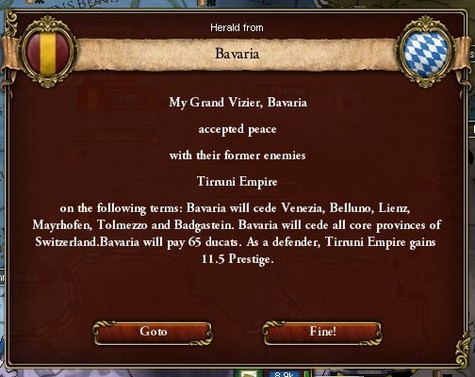

The city didn’t hold out very long, and with the Hanoverian army still weeks away, the Archduke of Bavaria was forced to make peace with Tirruni. And as expected, the treaty wasn’t very favourable to him, with Bavaria ceding the rest of its Italian territories to the Emperor in return for peace.

Across the Mediterranean, meanwhile, the Andalusi suffered another blow with the sudden loss of Fes. The city had held out for mere weeks before collapsing to the Berber onslaught, its defenses already badly damaged by the earlier siege.

And with Fes recaptured, there was no doubt that the Berber army would be heading southward before much longer, bent on lifting the siege of Marrakesh. Word of the fall of Fes reached Qadis before long, and at the insistence of the Majlis, Grand Vizier Zulfiqar agreed to send reinforcements to the Majlisi Guard, which was nos numerically-inferior to the Berber force.

Unfortunately, it would not be so easy.

The naval expansion program launched by the Almoravids had begun paying off, it would seem, because a small skirmish between Andalusi and Berber shipping in the straits quickly escalated into a massive naval battle. The Majlisi Fleet could hold its own against equal numbers, but when faced with a navy twice its size, there was simply no chance of emerging victorious.

So with the battle quickly devolving into a stalemate, the Grand Admiral gave the order to retreat, not willing to see his life’s work sunk to the bottom of the straits. The Majlisi Guard were on their own.

As far as Sheikh Fadhil was concerned, however, he’d always been on his own. The siege of Marrakesh had stretched on for months now, and he was done waiting, giving the command to assault the walls of the city.

And as the capital of the Almoravid Empire, the garrison defending Marrakesh was very large, standing 9000-strong. Fierce fighting broke out all along the parapets as the Andalusi poured into the breached walls in strength, with thousands of soldiers firing blindly, slashing mercilessly, grappling and wrestling and struggling in desperate attempts to outlive one another.

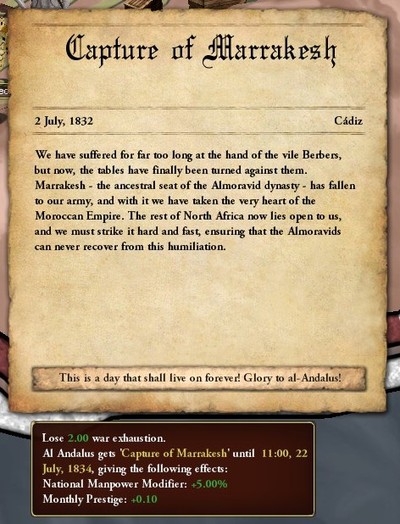

In the end, numbers would make all the difference, as the numerically-superior Andalusi forces overwhelmed, surrounded and massacred the defenders, though not without significant losses of their own. The rest of Marrakesh fell not long after, and with blood still hot and sticky on their faces, the Andalusi proceeded to plunder the renowned city.

Nestled amongst mountains and widely known as the ‘isolated city’, Marrakesh was famous for its privileged position as the ancestral seat of the Almoravid dynasty, its strictly-enforced ban on the entry of any foreigners, and its legendary hall of trophies and relics pillaged from distant lands - relics which include the Mascapaicha from Gharbia, the Benin Bronzes from Benin, jewelled busts of the earliest Jizrunid kings from al-Andalus, the Rosetta Stone from Egypt, the Koh-i-Noor from India and countless others. The city had never been besieged before, much less captured and desecrated, earning the victorious Andalusi soldiers fame and glory all across Europe.

As for Sheikh Fadhil, born into lush linens but made in the harsh mountains of north Africa, his feats would ensure the immortality of his name.

News of the fall of Marrakesh quickly travelled across the straits, sending Qadis into havoc as celebrations broke out all across the capital, and spreading from there to the rest of al-Andalus. In fact, several prominent politicians used the historic victory to urge the Grand Vizier to send another army into north Africa, to ensure that it was not won in vain.

And Zulfiqar, hoping to retain Marrakesh long enough to open negotiations with the Almoravid Sultan, agreed to attempt just that.

Unfortunately, this attempt to cross the straits ended much like the last - with the Majlisi Fleet forced to retreat after being intercepted by the Almoravid Navy. And even after the fleet had docked in Qadis, some fifty Berber warships continued to patrol the straits, refusing to risk any more crossings.

Back at Marrakesh, meanwhile, the Majlisi Guard didn’t have much time to revel in their victory. Within hours of capturing the city, Sheikh Fadhil began making preparations to meet the advancing Berber army, determined to defend his conquest at any costs.

The reckoning arrived in the dying days of 1832, with 55000 Berbers bearing down on Marrakesh, clashing with the 15000 Andalusi below its inscribed walls. The battle for Morocco had begun.

Even as the Andalusi and Berbers met in furious battle, however, a momentous declaration was being made in Smolensk. Surrounded by her advisors and ministers, along with several brown-skinned foreigners with forked beards and colourful fezzes, Empress Dobroslava Rurikid announced to her court that an alliance had been wrought with Morocco.

And with that, Russia finally enters the Tirruni Wars.