Part 98: Stately Quadrille

Chapter 18 - Stately Quadrille - 1904 to 1909The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were unstable and shaky, with the Great Powers jostling for influence and land in a carefully-balanced concert, one that was designed to prevent the escalation of tensions, to avert the eruption of crises, to avoid the outbreak of world-spanning warfare. And since the late 1880s, that system had actually worked, with the Peace of Narbuna reigning across the width of Europe.

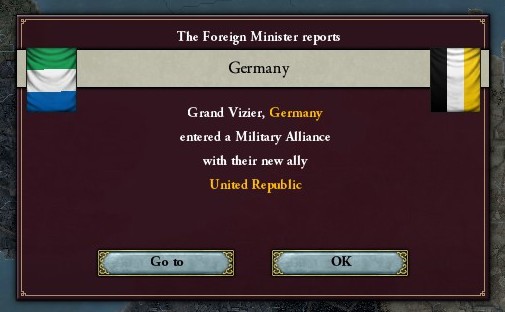

With the formation of Germany, however, the fragile peace immediately gave way to a scramble for allies and supporters - and thus begins the Stately Quadrille, a tenuous dance between empires as they fortify their borders, expand their arsenals and prepare for the war to come.

By the twentieth century, Germany had been ravaged by invaders and infighting for decades, forced to capitulate and disarm in a string of conflicts that stretched back to Tirruni Wars. But those same kingdoms and duchies had weathered through the storms, and with the defeat and annexation of the SGU, the Republic of Germany suddenly dominated vast swathes of Central Europe. And without hesitation, it immediately began to test its newfound strength.

A scant few weeks after unification, North German troops crossed the Alps in an undeclared invasion of Italy, ostensibly to “secure their new border”.

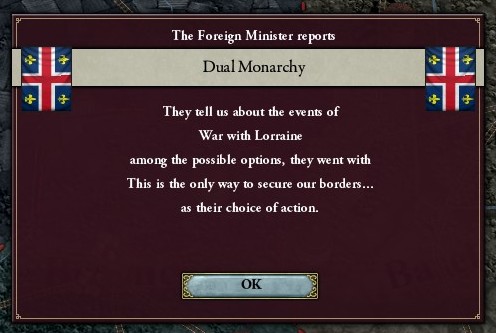

The neighbouring empires were still taken aback by the sudden disruption in the balance of power, but they quickly responded in kind. The Dual Monarchy launched an invasion of Lorraine - one of the most populous, richest and peaceful nations of Europe - to secure their own border with Germany, claiming that the mere existence of Lorraine put their empire at risk.

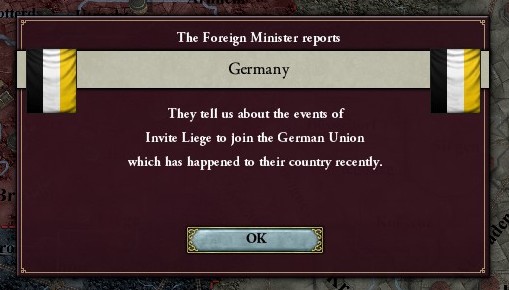

At the same time, war was being waged behind closed doors. Diplomats were dispatched from Hanover - the new capital of the German Republic - in March of 1904, travelling to the Archbishopric of Liege with an offer to join their union, with the diplomats claiming that the Dual Monarchy was planning an invasion of the Low Country.

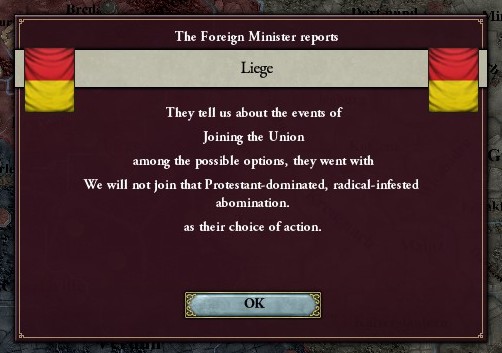

The Archbishop wouldn’t hear a single word from the emissary, however. It was bad enough that this new “German Union” was a republic, but a republic dominated by protestants, that was simply too far.

Ambassadors from Paris and Smolensk arrived at Liege a few weeks later, guaranteeing the Archbishopric’s sovereignty against the warmongering Germans. And it didn’t end there, with both nations reaffirming their own alliance in a public ceremony shortly afterwards.

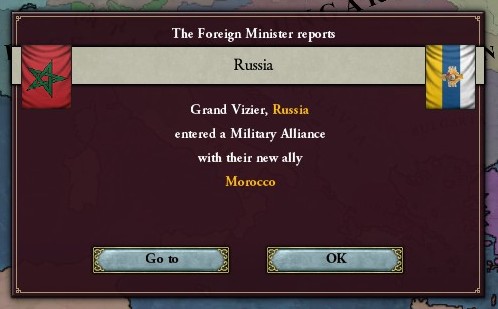

Envoys were also dispatched to Marrakesh, inviting Morocco to re-join their alliance bloc. The Almoravid Sultan immediately accepted the offer, keen to regain his standing on the international stage, and thus re-establishing the Congressional Coalition of Morocco, Russia and the Dual Monarchy.

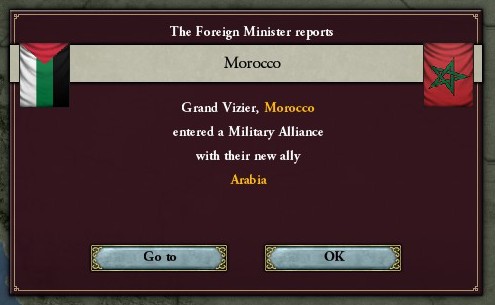

Emboldened by his recent victories and backed by his new allies, the Sultan of Morocco began exerting his influence across the Mediterranean once again, negotiating pacts and forging alliances for the first time since the Continental War.

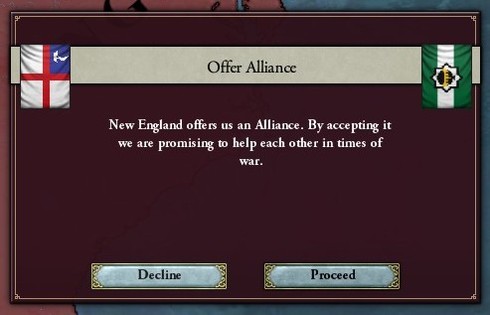

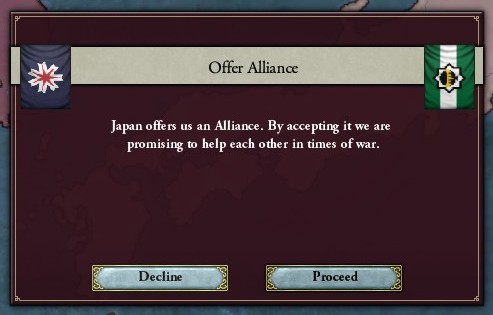

The reformation of the Congressional Coalition meant that the newly-formed Republic of Germany was surrounded by enemies in the east and west alike, not the best strategic position to be in. So the Germans sought to retaliate by forming their own alliances with other Great Powers - and first on their list was, inevitably, Al Andalus.

In fact, Al Andalus had many nations courting her for alliances and trade deals and friendships. The world still remembered the vicious battles fought during the Continental War, when the Andalusi had single-handedly repelled the combined forces of Morocco, Russia and the Dual Monarchy, forcing them to sign their carefully-crafted Treaty of Narbuna in a resounding military and diplomatic victory. Al Andalus had been quiet and isolationist since then, but they would still make a mighty ally in the wars to come, there was little doubt about that much.

All of these offers of alliance were rejected, however. The Andalusi themselves had other ideas.

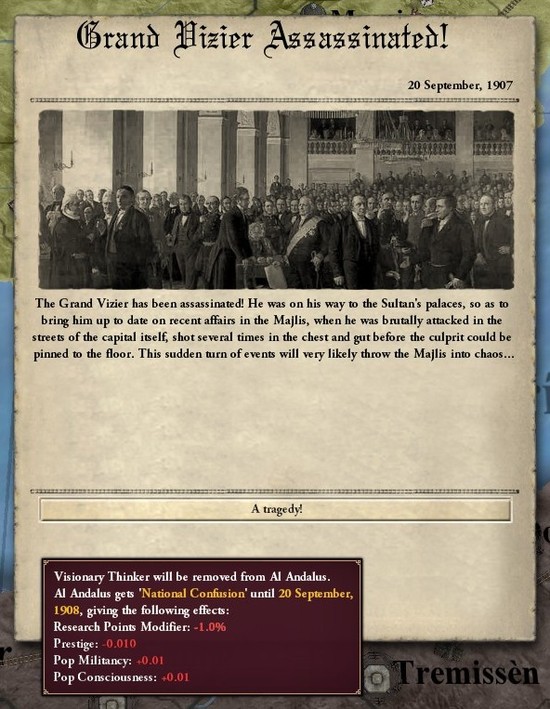

The past decade had been difficult on Al Andalus, with four Grand Viziers elected, consecrated and assassinated in the space of five years. The old guard were not taking to socialism very easily, that much was apparent to see.

But even after the death of their most ambitious and capable leader yet - Grand Vizier Rajul Majnun Mujamad - the reds refused to keel. After a brief period of infighting, another figure rose to dominate the Reformed Socialists, using his charm, wealth and family name to wheedle his way into the upper ranks of the government. And on the summer solstice of 1904, Mahmud Majnun Mujamad was proclaimed to be the new Grand Vizier of Al Andalus.

Mahmud was distantly related to his predecessor, Rajul Mujamad, but that was where their similarities end. Rajul and Mahmud had very different visions as to the future of socialism in Al Andalus, with the former advocating a hardline stance, demanding an end to imperialism and striving for social reform. Mahmud was much more flexible in his ideals, preferring to make concessions and forge alliances with other parties in the Majlis, and this often put him at odds with his elder cousin. Mahmud’s speeches had always gone ignored, however, nobody gave a whit about policies or legislation. Until now.

The Red Vizier had enjoyed his days in the sun, but he was dead and buried now, and it was Mahmud’s time to shine.

An even before taking office, the new Grand Vizier had crises to tackle and fires to quench. The first of these fires was the Indian Uprising, a mass rebellion that saw millions of Indians mutiny against commanders, resist colonial authorities, launch political assassinations, instigate riots and provoke confrontations and incite melees. Before anyone knew what had happened, the Andalusi Raj was engulfed in the flames of revolution.

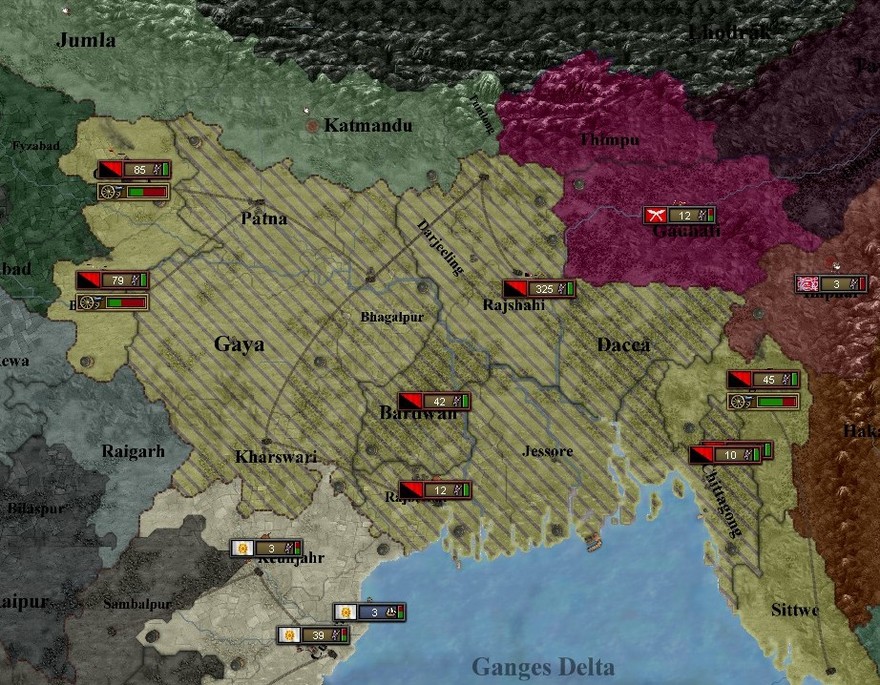

The response from Qadis was turgid and slow, owing to the political troubles at home, but Mahmud wasted no time in dispatched an expeditionary force to quell the uprising upon being declared Grand Vizier. A large force numbering around 20,000 trained and tried soldiers, almost entirely Andalusi in composition, landed along the banks of Jessore in the dying days of 1904.

And within minutes, they were surrounded by thousands of Indians, screaming and shouting and shrieking in a dozen different tongues as they swarmed across the sands and seized the beachheads.

The battle of Jessore would rage for two weeks, interrupted only by feigned retreats and mock surrenders, with any real attempts at mediation quickly descending into brawls and skirmishes. The Andalusi were outnumbered almost 5 to 1, but they were also better trained and better armed, with the Indian militias wielding outdated guns for the most part, or even scythes and swords amongst the lesser ranks.

And after fortifying the beaches and repelling the first attack, the Andalusi were able to gradually gain ground on the enemy, slowly pushing them northwards and seizing a string of nearby fortresses and encampments. When the signal for mass retreat was finally given, tens of thousands of Indian corpses littered the battlefield of Jessore, their blood staining the sands a brilliant shade of crimson - one that would not wash away anytime soon.

This was just the beginning of a campaign that would stretch across years and cost millions in lives, however. And with the Andalusi distracted by the struggle to retain their colonies, they were forced to pull their troops back from neighbouring native powers, allowing their colonial rivals to quickly expand their influence in Gondwana, Delhi, Orissa and the Bengal.

The socialists didn’t intervene or protest when the Moroccans and Japanese sent their own troops to garrison Delhi and Nagpur, they couldn’t care less, and they wouldn’t have been able to do much about it even if they could.

Why? Because the Indian Uprising wasn’t the only battle that they were fighting, it wasn’t even the most important, not when there were enemies threatening to topple them in the very streets of Qadis - the Communists.

For a brief period during the reign of the Red Vizier, the left-wing organisations and unions were united under common leadership. That unity disintegrated with the assassination of Rajul, however, and the gulf between socialism and communism in Al Andalus had widened to cavernous depths since then. Blows between the two blocs became increasingly frequent as Mahmud’s ineptitude became apparent, with the communists and radical socialists claiming that the Reformed Socialists had “betrayed the ideals and standards of socialism, instead preferring to walk on the backs of workers and labourers all across the country as they traipse about high society”, according to a prominent underground newsletter that was making the circuits.

And it wasn’t completely untrue. It hadn’t happened overnight, but the Reformed Socialists were steeped in corruption and hypocrisy, so it wasn’t much of a surprise when thousands of socialists abandoned the party and defected to illegal communist organisations.

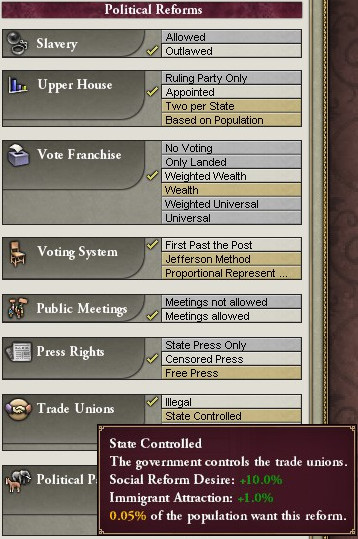

Desperate to curb this tide of defections, Grand Vizier Mahmud immediately began acting against this radical branch of socialism, banning and forbidding the mere mention of Communism as a legitimate political threat. The Grand Vizier knew that fear was not enough to maintain his rule, not after the recent string of political assassinations, so he also announced his intention to launch a new series of reforms, starting with the legalisation of state-controlled labour unions.

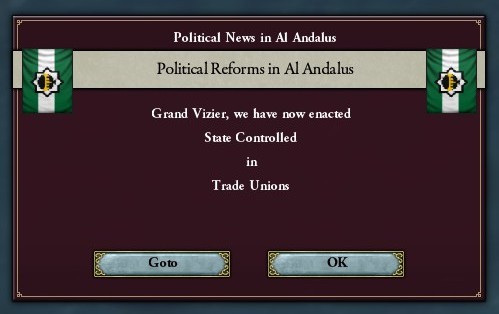

Whilst the Grand Vizier struggled against the rising tide of radical sympathies, the wars - or skirmishes, to put it more accurately - in Europe came to an end. As expected, both the German Republic and the Dual Monarchy quickly crushed any resistance to their invasions, with the former annexing the German-speaking parts of Italy, and the latter absorbing Lorraine in its entirety.

Germany and the Dual Monarchy now shared a border that stretched almost four hundred miles of cavernous valley and rushing river and immense mountain, from the Archishop’s seat of Liege in the north to the turbulent city of Bern in the south.

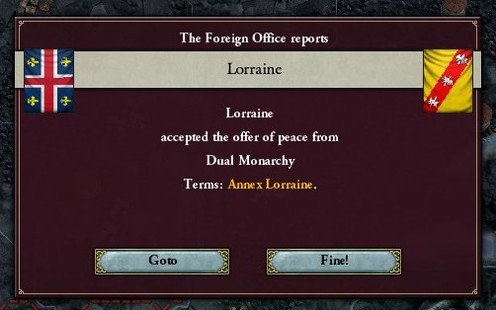

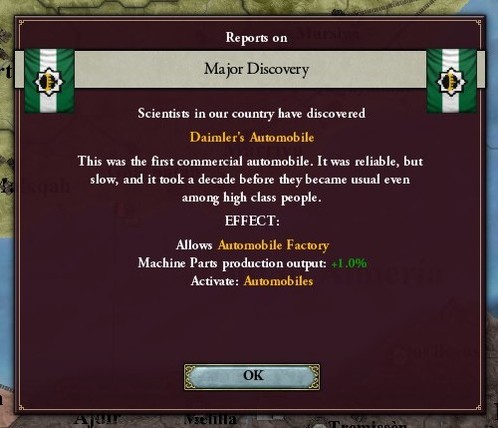

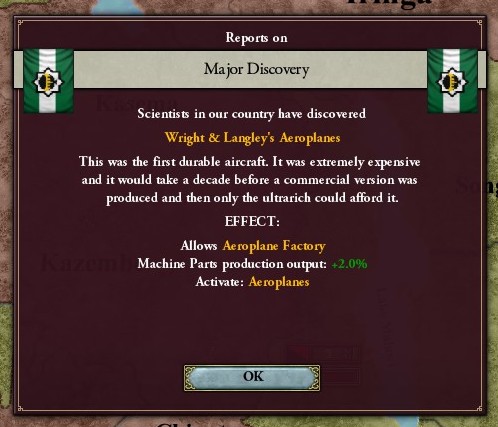

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, the instability and volatility that had engulfed the peninsula did little to stem the surge of technological advancements. In fact, if anything it fuelled them, with a number of Andalusi pioneers rising to global prominence as they devised and patented a series of extraordinary inventions, from telephones to automobiles to zeppelins.

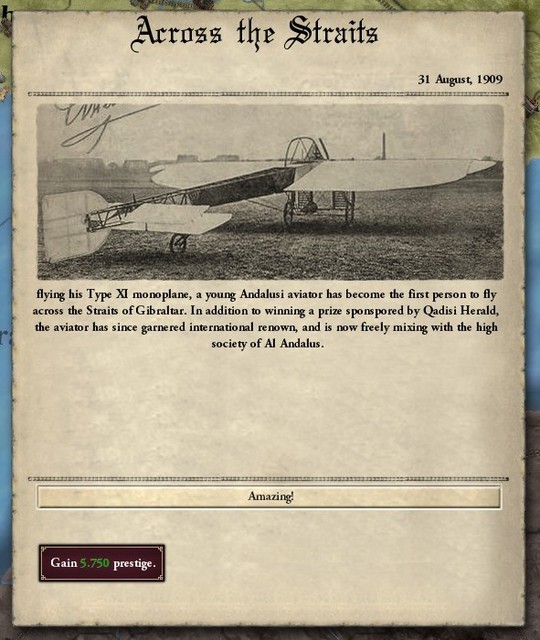

This was the Age of Inventions, and the Andalusi were at the forefront of it. Amongst the most famous of these innovations was undoubtedly the aeroplane, with two brothers from Tulaytullah devoting years of research and funds to the design and construction of the Firnas, the first aircraft to sustain heavier-than-air flight.

This astounding achievement would spark an aviation frenzy all across Europe, with the two brothers staging a series of dazzling demonstrations that culminated in a flight across the Straits of Gibraltar, captivating and awing commoners and politicians alike.

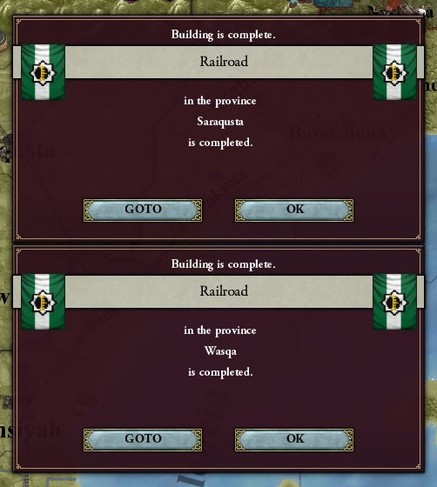

Grand Vizier Mahmud, on the other hand, continued to tread flimsy ground as he struggled to appease the moderates and curtail the radicals in his party. His promised reforms were brought to a screeching halt by a Moderate-Royalist-Sultanic coalition in the Majlis al-Shura, but the Grand Vizier was able to continue the development platform espoused by the Reformed Socialists by approving the construction of several hundreds of miles worth of railway in northern Iberia, along with several diesel-powered locomotives to run the lines between León and Qattalun.

And a few months later, he proudly the announced the completion of another line of expensive fortifications, this time dubbed the “Pillars of Gibraltar”. The Pillars featured a continuous ring of fortresses that stretched along the banks of the Straits, armed with colossal artillery and coastal batteries, manned by thousands of volunteer soldiers, and all but impregnable to invasions from the south.

At long last, Mahmud insisted in a speech to the viziers and nobles of the Majlis, the security of Al Andalus was assured.

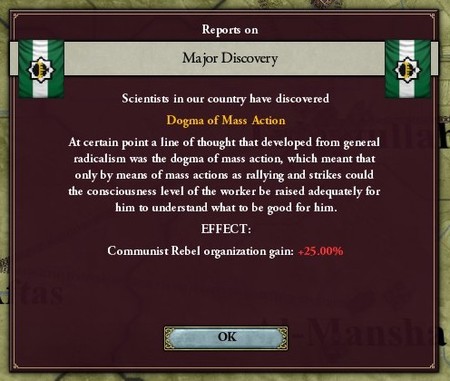

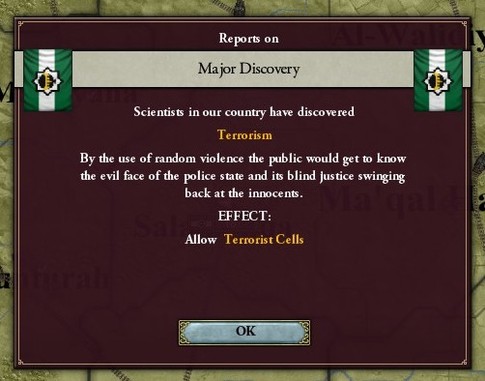

For every enemy that threatens Andalusia’s borders, however, three more look to topple the government from within. Despite the Grand Vizier’s best efforts, the communist movement was quickly gaining traction amongst the masses, with the rabble-rousers and demagogues now openly calling for coordinated rallies and demonstrations, for the intimidation of capitalists and aristocrats, for the overthrow of the Reformed Socialists and Majlis al-Shura — by any means necessary.

Across the width of the world, meanwhile, the campaign in Andalusi India had gradually gained ground over the past few years. Despite several early losses to the Indian militias, the Expeditionary Force was able to seize and fortify the Bengal Delta after a series of bloody battles along the banks of the river, and once reinforcements arrived from Africa (armed and trained by the Khedive), they were able to push out and begin recapturing their lost territories.

After four years of asymmetric warfare and scorched-earth tactics, the fighting finally culminated in the battle of Rajshahi in the early hours of a winter morning, deep into 1907.

The Andalusi were massively outnumbered, but that wasn’t out of the ordinary, with their superiority in arms and professionalism overwhelming the Indian advantage in numbers thus far.

The rebels had fortified Rajshahi in anticipation of the battle, but they emerged from the city as the Andalusi marched on it, intent on finally halting their advance. Immediately upon sighting each other, guns exploded and bullets were exchanged, with bodies dropping to the mud as the two armies clashed beneath the medieval walls of the city. The battle raged in a great semi-circle around the northern half of Rajshahi, featuring heroic charges and assaults in some parts, devolving into hand-to-hand brawls in others, and famously witnessing the suicide of thousands of rebels as they blew themselves apart in the hope of taking the Andalusi leadership with them.

This was their last stand, this was where the entire remaining strength of the Indian Uprising stood, the remnants of a continent-spanning revolution that had begun as a minor demonstration in the streets of Rajbalhat.

And this is where it was ended, with hundreds of thousands killed or wounded below the walls of the city.

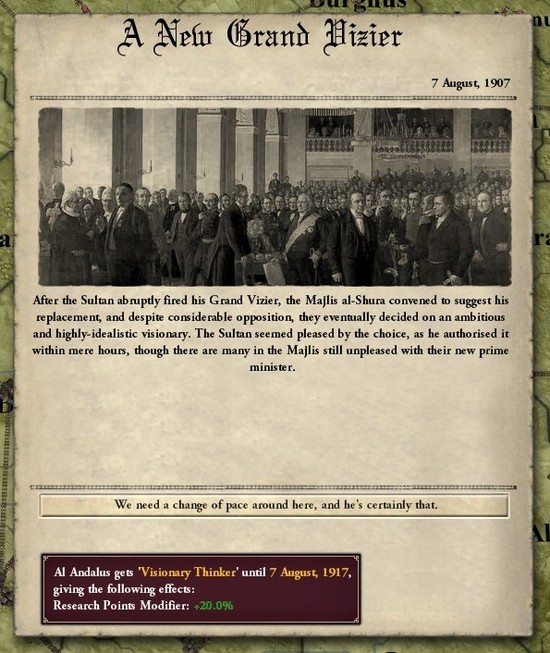

Three months after the battle of Rajshahi, order was finally restored to the Andalusi Raj, with the commanders dispatching telegrams carrying word of their victory to Qadis. Before it even reached the metropolis of Al Andalus, however, the victory was tempered by unwelcome news…

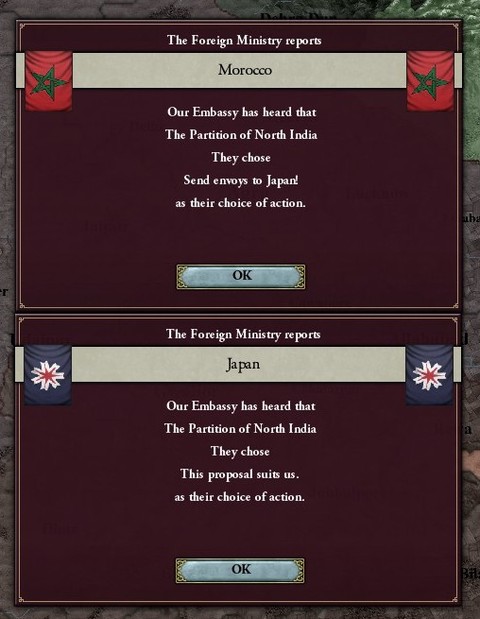

Whilst the Andalusi were struggling to maintain their hard-won colonies, Morocco and Japan had been conspiring to expand their own. Diplomats from the two empires met in a series of meetings over the course of 1907 to finally partition the remaining North Indian principalities amongst themselves, eventually reaching a settlement whereby Japan annexed the highly-lucrative basin of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, whilst Morocco was granted free rein to invade Gondwana and Orissa.

By the dying days of the Indian Uprising, the papers were all signed and dusted, without even the slightest acknowledgement from Al Andalus.

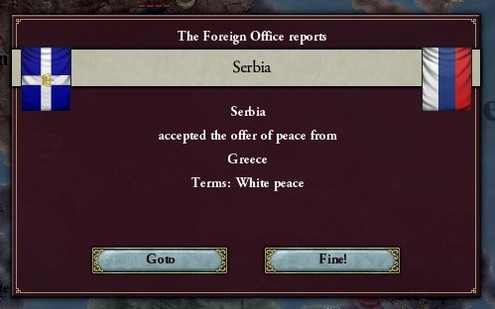

The socialists might not care much about colonial politics, but the other parties of the Majlis were immediately up in arms, roaring and bellowing in protest of the humiliating isolation enforced by the Reformed Socialists. Before the Grand Vizier could respond or retaliate, however, more news arrived from across the Mediterranean, where Serbia had defied expectations and repelled both Greece and Bulgaria.

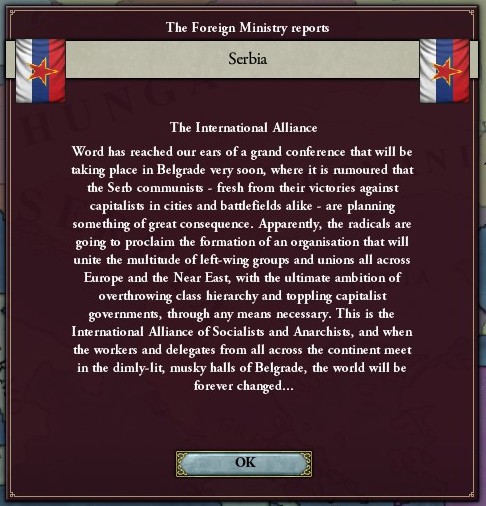

More than that, the radicals had actually defeated the Greeks and Bulgarians on the battlefield, launching counter-invasions of their own, counter-invasions that were markedly more successful than their antecedent. Despite the constant influx of money and guns from the Congressional Coalition, the Serbian communists managed to capture Athens and Sofia in the fall of 1908, bringing the First Struggle to a decisive conclusion.

With their forces crushed and capitals fallen, the Greeks and Bulgarians were forced to surrender unconditionally. Diplomats were dispatched to negotiate peace settlements with the Serbs, but to the surprise of the vanquished kings and prime ministers, those same diplomats were expelled without an audience.

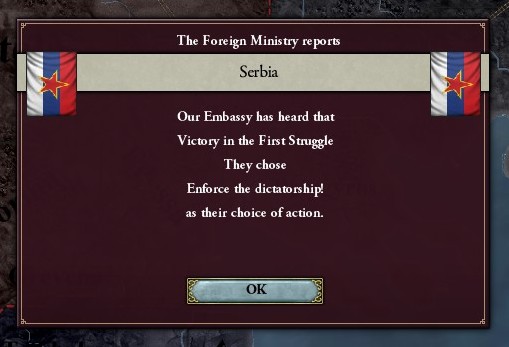

Instead, the Serbs supervised the abolition of private enterprises and bourgeoisie operations, conducted the organisation of democratically-elected councils, and personally installed a renowned revolutionary as the “Dictator of the Proletariat”.

The radicals were there to stay, it would seem.

The Great Powers of Europe were left dumbstruck and paralysed, with the communist victory immediately inciting the outbreak of a wave of mass riots and rebellions all across the continent.

And the victorious leadership of Serbia only further fanned these flames, with the voices of a hundred communists broadcasted across Europe as they called for workers and labourers to take to the streets, to overthrow their capitalists oppressors, to topple their governments and seize the means of production and achieve socialism through the only means possible — revolution.

And that was precisely what happened.

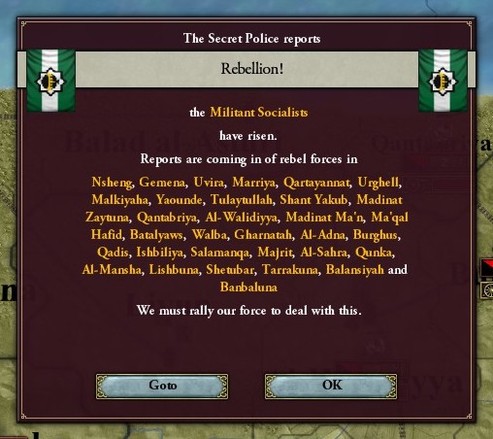

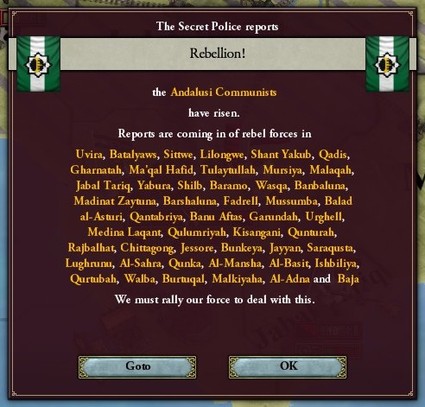

In the months that followed, a series of riots and confrontations escalated in cities dotting Iberia, with demonstrations and protests turning violent more often than not. It was becoming increasingly clear that these socialists weren’t taking their orders from Qadis, not anymore, they were listening to the words that surged forth from Belgrade, listening and obeying and acting.

The Grand Vizier refused to surrender to these radicals, but he had already lost the support of the poor, quickly followed by the workers and labourers, along with the unions and guilds shortly afterwards, before finally being abandoned by his own party. And in the winter months of 1908, he was finally relieved from his esteemed office when a gang of radical communists surrounded, kidnapped and murdered him in the very streets of the capital.

And with that, the tinderbox was well and truly set aflame.

“Peace, prosperity and plentifulness.”

The irony of those words only becomes clearer as rebellions and revolts erupt all across the peninsula, with the Sultanate of Al Andalus descending into its most divided and fractured years in almost a century. Martial law is declared and the army is mobilised, but unbeknownst to the astute viziers and charming politicians of Qadis, this is only the beginning.

Fresh from their victory in the First Struggle, as the Serbian communists would later call their wars against neighbouring Balkan powers, the communist leadership proudly announce the organisation of a grand conference in Belgrade. This conference would host hundreds of left-wing parties and organisations from dozens of nations across Europe and the Near East, seeking to unite the divided and disenfranchised masses into a single powerful league, one that would ignite terror in powers great and small alike. The Red Vanguard has been forged, and is ready to march to war.

The International League of Socialists and Anarchists would lay the foundations for a political and military alliance that transcends borders and boundaries, with the revolutionaries joining forces against a common enemy and uniting under a common flag. The words of the revolution ring in the streets and alleyways of Europe, sung in thousands of loud and hopeful voices, by tens of thousands of workers marching to break their shackles.

A red sun is rising, and when it sets on the world, it will be one forever changed.

World map: