Part 28: January 25 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, there will be our coverage of the performing of every Shakespeare play at the Globe theatre which will be done for child literacy charity. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twenty-eighth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode, we discussed the surrender of the Genoese against the Dutch.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twenty-eighth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode, we discussed the surrender of the Genoese against the Dutch. And by now, the Dutch were well secured in the Mediterranean. With the Polish holding back from an actual offense, the Dutch could now turn to the British who were intensifying their attacks every season. In the channel in 1748, the Dutch had two third rate ships of the line, a first rate, several fifth rates, and perhaps a half dozen supporting vessels. In the port of Le Havre, another half dozen carronade frigates were put into production. Inexpensive, fast and powerful, carronade frigates were an economical and quick to construct ship. Like a brig however, the carronade Frigate was prone to exploding when under intense fire, though as a more modern design, it was slightly reinforced against such an incident.

And by now, the Dutch were well secured in the Mediterranean. With the Polish holding back from an actual offense, the Dutch could now turn to the British who were intensifying their attacks every season. In the channel in 1748, the Dutch had two third rate ships of the line, a first rate, several fifth rates, and perhaps a half dozen supporting vessels. In the port of Le Havre, another half dozen carronade frigates were put into production. Inexpensive, fast and powerful, carronade frigates were an economical and quick to construct ship. Like a brig however, the carronade Frigate was prone to exploding when under intense fire, though as a more modern design, it was slightly reinforced against such an incident.

The carronade was a half length, double weighted cannon. Firing a much heavier round from a relatively light chassis for the thirty-two pound ball gave the carronade tremendous close range power, but the shortened barrel dropped their range considerably.

This fleet often came across a popular British composition, that being a single second rate ship of the line supported by a sloop or brig. The smaller ship would ensure that ships could not use their superior speed and manueverability to keep the larger second rate under fire without retaliation from the fore or aft while the second rate would try to damage or destroy the larger Dutch frigates or ships of the line. While invariably, the Dutch would surround and destroy these vessels, they only managed to capture a single second rate in the channel, the Glatton by the end of 1748. All the others had managed to fight until sunk causing heavy damage to the Dutch fleet before being scuttled. Even the Glatton had nearly sunk before surrendering.

This fleet often came across a popular British composition, that being a single second rate ship of the line supported by a sloop or brig. The smaller ship would ensure that ships could not use their superior speed and manueverability to keep the larger second rate under fire without retaliation from the fore or aft while the second rate would try to damage or destroy the larger Dutch frigates or ships of the line. While invariably, the Dutch would surround and destroy these vessels, they only managed to capture a single second rate in the channel, the Glatton by the end of 1748. All the others had managed to fight until sunk causing heavy damage to the Dutch fleet before being scuttled. Even the Glatton had nearly sunk before surrendering.

The Glatton is surrounded by Dutch ships. Many other such second rate ships were sunk, but the Glatton's captain had a fit of panic and surrendered his ship.

One such patrol actual broke through the Dutch defenses on the western sector of the channel, chasing away defending Dutch ships all the way to Portugal. This second and fourth rate combination managed to drive back the Dutch third and her support from the western channel, opening a potential hole through which the British could invade next season. The Dutch hoped their third would evade the British fleet to return to a blockade, and that the returning Dutch fleet would capture or sink them to prevent them driving away the Dutch defenses a second time.

One such patrol actual broke through the Dutch defenses on the western sector of the channel, chasing away defending Dutch ships all the way to Portugal. This second and fourth rate combination managed to drive back the Dutch third and her support from the western channel, opening a potential hole through which the British could invade next season. The Dutch hoped their third would evade the British fleet to return to a blockade, and that the returning Dutch fleet would capture or sink them to prevent them driving away the Dutch defenses a second time.

The Dutch fleet along the west of the channel was forced back ship by ship by an assault by British ships of the line. The weight of previous British naval attacks had been on the East end of the Channel, so the powerful breakthrough along the West caught them off guard.

The Dutch fleet led by the Westfreisland was far too large for the British second rate, the Hiberion to engage. It was almost inevitable that the British fleet would opt for retreating back to the now undefended channel where they could tie up more Dutch defensive ships for a season. Possibly long enough to make a crossing before the Dutch defenses could make it back North into the channel. Curen, still admiral of the Dutch Atlantic fleet sought to redeem himself. After rumours of cowardice in his battle against the British near America, Admiral Curen hoped to hold onto his title and position even though men had begun lobbying for his position after the Leeuwerik, the Dutch first rate, had been given to Admiral Johan Zoutman.

The Dutch fleet led by the Westfreisland was far too large for the British second rate, the Hiberion to engage. It was almost inevitable that the British fleet would opt for retreating back to the now undefended channel where they could tie up more Dutch defensive ships for a season. Possibly long enough to make a crossing before the Dutch defenses could make it back North into the channel. Curen, still admiral of the Dutch Atlantic fleet sought to redeem himself. After rumours of cowardice in his battle against the British near America, Admiral Curen hoped to hold onto his title and position even though men had begun lobbying for his position after the Leeuwerik, the Dutch first rate, had been given to Admiral Johan Zoutman.

Johan Zoutman later in life.

Likely knowing that a courageous assault on the British from the fore was not possible, simply because the British would retreat, he hoped that he could devise a plan which would allow a decisive victory with minimal casualties to his own forces. Curen knew the British ships were tasked with clearing away the channel fleet, but had contacted trade ships that had been fleeing from them as well. Smelling an over ambitious captain out for a prize capture, Curen sent his trade ships, them being heavily armed Fluyts and captured Spanish galleons to lure in the British. The four trade ships were rated at a similar value to a fifth rate or weak fourth rate ship. Just few and weak enough for a second rate and an attendant fourth to capture in a terrific fight, but far too valuable to pass up.

Likely knowing that a courageous assault on the British from the fore was not possible, simply because the British would retreat, he hoped that he could devise a plan which would allow a decisive victory with minimal casualties to his own forces. Curen knew the British ships were tasked with clearing away the channel fleet, but had contacted trade ships that had been fleeing from them as well. Smelling an over ambitious captain out for a prize capture, Curen sent his trade ships, them being heavily armed Fluyts and captured Spanish galleons to lure in the British. The four trade ships were rated at a similar value to a fifth rate or weak fourth rate ship. Just few and weak enough for a second rate and an attendant fourth to capture in a terrific fight, but far too valuable to pass up.

The Galleons and Fluyts were tough, powerful ships able to defend themselves against weaker ships and pirates, but the British second rate was more than a match. As valuable ships, they made excellent bait, and with four of them, they were powerful enough to allay suspicion of a trap.

The Dutch fleet ordered their trade ships to keep near the coast of Portugal while the main fleet kept further behind. Sloops and other small ships were tasked with keep the fleets within sight of their signal flags by relaying coordinates and orders. The Dutch were waiting for the weather to turn as they wanted. This came about after a great amount of cat and mouse chasing, close calls and near discover on a foggy day in September.

The Dutch fleet ordered their trade ships to keep near the coast of Portugal while the main fleet kept further behind. Sloops and other small ships were tasked with keep the fleets within sight of their signal flags by relaying coordinates and orders. The Dutch were waiting for the weather to turn as they wanted. This came about after a great amount of cat and mouse chasing, close calls and near discover on a foggy day in September.

The Westfriesland moving into action, finally receiving the weather they had waited for. A few small sloops between their trade ships and the main fleet kept the two groups in contact with one another.

With a fog coming in, and refusing to lift by noon, the Dutch trade vessels had come in as close as possible to the British ships. Curen was waiting very specifically just west of Lisbon, where the Dutch trade ships would lure the British. With the fog, so dense that the sailors and lookouts could barely see a kilometer away would not see the Dutch navy before they were within close distance.

With a fog coming in, and refusing to lift by noon, the Dutch trade vessels had come in as close as possible to the British ships. Curen was waiting very specifically just west of Lisbon, where the Dutch trade ships would lure the British. With the fog, so dense that the sailors and lookouts could barely see a kilometer away would not see the Dutch navy before they were within close distance.

The Hibernia chasing ships through the fog. The crew could not see beyond the Dutch trade ships.

The Dutch trade vessels were fleeing in a slow and chaotic manner. Normally well capable of outpacing the British second rate, they wanted to make sure the British did not lose them. A more cautious captain would have sensed the trap, but the captain of the second rate Hibernia was far too impetuous. Following the Dutch trade ships directly, after an hour of chasing, their lookout called back a chilling report. Dutch ships of the line backed by a considerable number of frigates. Slower than the Dutch third rates, the Hibernia had no choice but to fight.

The Dutch trade vessels were fleeing in a slow and chaotic manner. Normally well capable of outpacing the British second rate, they wanted to make sure the British did not lose them. A more cautious captain would have sensed the trap, but the captain of the second rate Hibernia was far too impetuous. Following the Dutch trade ships directly, after an hour of chasing, their lookout called back a chilling report. Dutch ships of the line backed by a considerable number of frigates. Slower than the Dutch third rates, the Hibernia had no choice but to fight.

The Dutch come across the British in the fog.

The heavily armed Dutch trade ships immediately came about, the British second rate now completely out of options was quickly swarmed over by the many Dutch ships. Their ships of the line managed volleys against her as well, completely devastating her. After demolishing the majority of their guns and killing many of their crew, Curen himself boarded the fleeing Hibernia, capturing it relatively intact.

The heavily armed Dutch trade ships immediately came about, the British second rate now completely out of options was quickly swarmed over by the many Dutch ships. Their ships of the line managed volleys against her as well, completely devastating her. After demolishing the majority of their guns and killing many of their crew, Curen himself boarded the fleeing Hibernia, capturing it relatively intact.

The Hibernia is devastated by Dutch cannon fire. The Westfreisland moves in to capture it.

This wasn’t enough to completely alleviate suspicion of his nature, but Curen was somewhat redeemed through his clever victory. The defeat of the British fleet allowed the Dutch to move their ships chased away from the channel back into a defensive position, stopping a 1748 invasion. While his own fleet would need retrofitting and more crew, especially for the captured second rate, the channel was safe from invasion for now.

This wasn’t enough to completely alleviate suspicion of his nature, but Curen was somewhat redeemed through his clever victory. The defeat of the British fleet allowed the Dutch to move their ships chased away from the channel back into a defensive position, stopping a 1748 invasion. While his own fleet would need retrofitting and more crew, especially for the captured second rate, the channel was safe from invasion for now.

Curen boards the Hibernia. Normally taking such a ship in a boarding action would have been a very brave move, but the Hibernia was on the verge of surrender already. While Curen's reputation was somewhat repaired, he would never manage the same level of respect as he would have wanted.

Back in the channel at least twice a year leading up until 1749, the British were probing and attacking the Dutch fleets around the channel. At the time, the Dutch had thought the were simply intensifying their probing attacks to prepare for an invasion. During 1748, this was likely their motivation. However, early in 1749, the Dutch fleets, spread across the channel, bruised, bloodied and constantly under attacks which prevented their repair were attacked by the full Polish fleet which had been keeping tabs on the Prussians. Their fleet contained at least three fourth rate ships, a multitude of frigates, and approximately a dozen briggs.

Back in the channel at least twice a year leading up until 1749, the British were probing and attacking the Dutch fleets around the channel. At the time, the Dutch had thought the were simply intensifying their probing attacks to prepare for an invasion. During 1748, this was likely their motivation. However, early in 1749, the Dutch fleets, spread across the channel, bruised, bloodied and constantly under attacks which prevented their repair were attacked by the full Polish fleet which had been keeping tabs on the Prussians. Their fleet contained at least three fourth rate ships, a multitude of frigates, and approximately a dozen briggs.

The Polish hope to break through the tired and hard pressed Dutch channel navy.

The Dutch had wished to send their large Atlantic fleet to oppose them around Prussia, but the Polish navy moved first, hoping to destroy the Dutch before those reinforcements could arrive, clearing the way for the British navy to sweep through. Instead of the large and well maintained Atlantic navy and their three third rates, large supporting frigate fleet and bomb ketches, the Dutch had to make do with the battered channel fleet, consisting of a near pristine first rate, a near sunk second rate, a third rate, a captured fourth rates, a fifth rate and a scant handful of supporting vessels.

The Dutch had wished to send their large Atlantic fleet to oppose them around Prussia, but the Polish navy moved first, hoping to destroy the Dutch before those reinforcements could arrive, clearing the way for the British navy to sweep through. Instead of the large and well maintained Atlantic navy and their three third rates, large supporting frigate fleet and bomb ketches, the Dutch had to make do with the battered channel fleet, consisting of a near pristine first rate, a near sunk second rate, a third rate, a captured fourth rates, a fifth rate and a scant handful of supporting vessels.

The Polish ships vastly outnumbered the Dutch. Unlike other situations where the Dutch found themselves outnumbered, the Polish navy did have several heavier rated ships.

These ships were led by Johan Zoutman, a surprisingly young Admiral. A keen and courageous Admiral, and one with near endless energy and brilliance, Zoutman had beaten out his elders for the position through his endless aggression. A former captain of the Wapen van Holland when it was stationed in the Mediterranean, and then a captured British fourth rate, Zoutman had a long history of daring and ambition. Backed by a keen mind for strategy and tactics, as well as a thorough knowledge of naval history, Zoutman was still a controversial choice. Despite his qualities, he had the major flaw of little command experience, and never any experience in leading more than a single vessel.

These ships were led by Johan Zoutman, a surprisingly young Admiral. A keen and courageous Admiral, and one with near endless energy and brilliance, Zoutman had beaten out his elders for the position through his endless aggression. A former captain of the Wapen van Holland when it was stationed in the Mediterranean, and then a captured British fourth rate, Zoutman had a long history of daring and ambition. Backed by a keen mind for strategy and tactics, as well as a thorough knowledge of naval history, Zoutman was still a controversial choice. Despite his qualities, he had the major flaw of little command experience, and never any experience in leading more than a single vessel.

The Dutch inexplicably named their first rate after a small bird, the Leeuweric.

Still powerful, the Dutch fleet did stand a strong chance against the Polish fleet. With only three ships of the line in their roster, if the Dutch could destroy them quickly, the supporting brigs and sloops would not be sufficient to answer to the Dutch first and third rate ships of the line. Under ideal circumstances, the Dutch second rate captured from the British would also be insurmountable to the Polish brigs, but it had been so heavily damaged in its capture that it would not have stood in the line with such immunity.

Still powerful, the Dutch fleet did stand a strong chance against the Polish fleet. With only three ships of the line in their roster, if the Dutch could destroy them quickly, the supporting brigs and sloops would not be sufficient to answer to the Dutch first and third rate ships of the line. Under ideal circumstances, the Dutch second rate captured from the British would also be insurmountable to the Polish brigs, but it had been so heavily damaged in its capture that it would not have stood in the line with such immunity.

A print of the Glatton. A medium ship on the border between a frigate and a ship of the line.

The Dutch discovered the Polish fleet as it advanced towards the Dutch, likely heading to the port of Rotterdam. As the Dutch had spread themselves thin to cover as much of the English channel as they possibly could, their ships were pulled into battle out of line forcing them to regroup West of the Polish attack. With the few supporting ships that had initially caught sight of the Polish fleet heading into the wind to meet up with their first rate and her supporting ships, and the Polish moving to mask that movement, it would take a considerable amount of time before these navies clashed.

The Dutch discovered the Polish fleet as it advanced towards the Dutch, likely heading to the port of Rotterdam. As the Dutch had spread themselves thin to cover as much of the English channel as they possibly could, their ships were pulled into battle out of line forcing them to regroup West of the Polish attack. With the few supporting ships that had initially caught sight of the Polish fleet heading into the wind to meet up with their first rate and her supporting ships, and the Polish moving to mask that movement, it would take a considerable amount of time before these navies clashed.

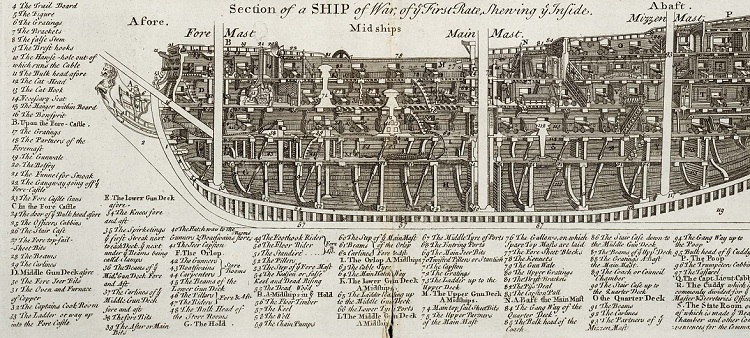

A part of a schematic for a first rate. Their massive size and high value made them fairly complex to build and design. With more fire power than entire armies, a first rate was similar to a star fort at sea, being the focus of the fleet's command, and the sturdiest source of firepower. So long as the Dutch had it, and the Polish had nothing to match it, the battle was not hopeless.

The Dutch were given a significant break while traveling into range which they used to assess the situation and plan. The Dutch had to focus on defeating the fourth rates, while preserving their third and first rate as much as possible. That would mean the Dutch would have to fire into the lead elements of the Polish navy for as long as possible before their superior numbers could be brought to bear, and the Dutch would need to expend her frigates to the fire of the fourth rate Polish ships. That exchange would probably leave the Dutch without support vessels leaving them without maneuverability to counter the faster remaining Polish brigs. To counter that, the Dutch would have to keep their remaining ships in a staggered formation rather than a line so that each ship could cover one another’s blind spot.

The Dutch were given a significant break while traveling into range which they used to assess the situation and plan. The Dutch had to focus on defeating the fourth rates, while preserving their third and first rate as much as possible. That would mean the Dutch would have to fire into the lead elements of the Polish navy for as long as possible before their superior numbers could be brought to bear, and the Dutch would need to expend her frigates to the fire of the fourth rate Polish ships. That exchange would probably leave the Dutch without support vessels leaving them without maneuverability to counter the faster remaining Polish brigs. To counter that, the Dutch would have to keep their remaining ships in a staggered formation rather than a line so that each ship could cover one another’s blind spot. The battle initiated when the Dutch had moved their fleet into a single formation. The Polish forced into the collective Dutch while struggling into the wind found the Dutch first through fourth rates turned with their broadsides to the fore of the Polish fourth rates, raking them from fore to stern with cannon fire. The lead fourth was forced to surrender, and soon after sunk from just a single crushing volley from the Dutch line.

The battle initiated when the Dutch had moved their fleet into a single formation. The Polish forced into the collective Dutch while struggling into the wind found the Dutch first through fourth rates turned with their broadsides to the fore of the Polish fourth rates, raking them from fore to stern with cannon fire. The lead fourth was forced to surrender, and soon after sunk from just a single crushing volley from the Dutch line.

The Dutch make their first pass against the Polish line. Crushing concentrated volleys against the Polish ships of the line cause the damage the Dutch needed to win the fight.

The Polish navy had to weather another pair of less concentrated volleys, taking significant damage on another fourth as they struggled into the wind. A pair of smaller vessels were also forced out of the fight in that initial clash. With those opening volleys, and a very favourable wind, the Dutch had secured an almost certain victory in the battle. Their first and third rate were untouched, and could have taken the entire remaining Polish fleet themselves.

The Polish navy had to weather another pair of less concentrated volleys, taking significant damage on another fourth as they struggled into the wind. A pair of smaller vessels were also forced out of the fight in that initial clash. With those opening volleys, and a very favourable wind, the Dutch had secured an almost certain victory in the battle. Their first and third rate were untouched, and could have taken the entire remaining Polish fleet themselves.

The Dutch continue to pummel the Polish lead ships as the Polish navy is forced to turn into the wind. The Dutch ships were putting enough weight into their volleys to rapidly take out the heaviest Polish ships.

This clash was going just as the Dutch had wanted, but once the Polish had caught up with the Dutch and were fully brought into the line, the Dutch could no longer fire without retaliation. Ships fought from point blank with one another, Dutch ships destroying everything that came alongside them.

This clash was going just as the Dutch had wanted, but once the Polish had caught up with the Dutch and were fully brought into the line, the Dutch could no longer fire without retaliation. Ships fought from point blank with one another, Dutch ships destroying everything that came alongside them.

The Dutch allow the battle to degenerate into a close range broadside contest. With far more resilient ships, far more cannons, the Dutch fleet could far more readily survive such a contest.

Carronade frigates, particularly capable at hitting lighter ships managed to blow apart the Polish bomb Ketch, which had thankfully failed to ignite any of the rigging or ropes aboard the Dutch ships. The heavy caliber shot fired from the carronade cannon was excellent at this form of close range brawl. Passing close in, the carronades destroyed many ships, before on was sunk in return. The other was forced to flee.

Carronade frigates, particularly capable at hitting lighter ships managed to blow apart the Polish bomb Ketch, which had thankfully failed to ignite any of the rigging or ropes aboard the Dutch ships. The heavy caliber shot fired from the carronade cannon was excellent at this form of close range brawl. Passing close in, the carronades destroyed many ships, before on was sunk in return. The other was forced to flee.

The Dutch manage to blow apart the Polish bomb ketch, an action which was a high priority.

These explosions killed the entire crew and destroyed the ship immediately, doing both with such violence that adjacent ships were put under risk. The highly destructible nature of the brigs led to one such situation where the captured and heavily damaged second rate British vessel, the Glatton blew apart a Polish brig. The violence of the explosion lit most of the Glatton on fire, forcing her to surrender.

These explosions killed the entire crew and destroyed the ship immediately, doing both with such violence that adjacent ships were put under risk. The highly destructible nature of the brigs led to one such situation where the captured and heavily damaged second rate British vessel, the Glatton blew apart a Polish brig. The violence of the explosion lit most of the Glatton on fire, forcing her to surrender.

A brig is blown apart within handshaking distance with the Glatton. The force of the explosion ignites the Glatton, destroyed many of her cannons and shocked most of her crew.

The Glatton at that stage had been in a close range gun fight with several of the Polish ships, some of them catching fire as well. Several could not escape, and yet more found themselves drifting into the blast radius. But a few minutes later, the Dutch second rate was blown apart, taking a Polish frigate with it, and lighting several other brigs alight. A terrible series of explosions took over a thousand lives, many from the retributive death knell of a small, unnamed brig.

The Glatton at that stage had been in a close range gun fight with several of the Polish ships, some of them catching fire as well. Several could not escape, and yet more found themselves drifting into the blast radius. But a few minutes later, the Dutch second rate was blown apart, taking a Polish frigate with it, and lighting several other brigs alight. A terrible series of explosions took over a thousand lives, many from the retributive death knell of a small, unnamed brig.

The Glatton explodes, destroying another Polish vessel. This occurred after yet more ships drifted into the conflagration and as these smaller damaged vessels were considerably lighter, they had also been blown apart expediting the destruction of the Glatton.

It was only fortunate for the Dutch that the Polish navy had been far larger than their own, prompting the Dutch to spread their larger and more powerful ships apart to provide one another better supporting fire. The Glatton was their only casualty of the terrible explosions that claimed half a dozen ships and their crews. This left the Polish navy unbelievably demoralized, the remainder of their fleet captured or burned by their crew to prevent capture.

It was only fortunate for the Dutch that the Polish navy had been far larger than their own, prompting the Dutch to spread their larger and more powerful ships apart to provide one another better supporting fire. The Glatton was their only casualty of the terrible explosions that claimed half a dozen ships and their crews. This left the Polish navy unbelievably demoralized, the remainder of their fleet captured or burned by their crew to prevent capture.

Distraught sailors, either out of valour or despair burn their brig to prevent their capture. Over a thousand sailors were lost at sea that day, many blown apart or burned alive rather than drowned or killed by cannon fire.

With the tremendous Polish fleet out of the way, the Dutch were fairly secure in the English channel and at sea in general. Their greatest concern was that the number of British second rate ships was increasing by the year. If British production, which saw the creation of two new second rates along with supporting frigates and brigs continued, the Dutch navy could very well find itself eroded into nothingness. Even by 1750, where the Dutch held clear dominance at sea, the British navy found itself courageous enough to raid their trade routes hampering the Dutch economy and forcing the Dutch away from the channel.

With the tremendous Polish fleet out of the way, the Dutch were fairly secure in the English channel and at sea in general. Their greatest concern was that the number of British second rate ships was increasing by the year. If British production, which saw the creation of two new second rates along with supporting frigates and brigs continued, the Dutch navy could very well find itself eroded into nothingness. Even by 1750, where the Dutch held clear dominance at sea, the British navy found itself courageous enough to raid their trade routes hampering the Dutch economy and forcing the Dutch away from the channel.

The Dutch manage to clear away the powerful Polish fleet, but their own ships are left battered and on the brink of destruction. If the British attacks intensify, it is possible that they will not be in condition to fight back.

Next we will be doing a live broadcast of the entire works of Shakespeare as performed at the Globe theater. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news before returning to Shakespeare for the rest of the evening. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.

Next we will be doing a live broadcast of the entire works of Shakespeare as performed at the Globe theater. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news before returning to Shakespeare for the rest of the evening. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.