Part 19: Act 1 – Hisao and Ableism

Update 17: Act 1 – Hisao and AbleismWe just finished Act 1 of 4. Each route shares a largely conventional three act structure over 1 through 4, and like any good first act, Act 1 sets the stage and introduces the important characters. Unlike most first acts, though, it has a thematic role most stories don’t need filled: it breaks down stereotypes.

"Disabled We Stand” posted:

[P]eople in wheelchairs repeatedly find that, when they have somebody pushing their chair, questions are addressed to their pusher rather than to them… Edwina McCarthy finds that this happens so frequently that it comes as something of a surprise when her presence is actually recognised: “At the greengrocer's the first time we went in they asked me what I wanted. I was a bit taken aback.” (And Derek adds wryly, “Quote. I got told to shut up, they were speaking to the young lady.”) “But in our local supermarket, some of the cashiers would ask Derek. And that's degrading.”

Trick question: why would you look at someone in a wheelchair, someone who otherwise looks perfectly ordinary, and talk only to the person pushing them? Go ahead, think of a reason.

I’ll wait.

Now go back, think about that reason, and tell me: was it that the person pushing the wheelchair was their caretaker? We don’t know jack about this situation. The person in the wheelchair could be asleep, or sick. They might be doing something else or talking to someone else, or they just might not want to talk. So did you guess that whoever was pushing the wheelchair was making decisions for the person in it? I’d bet most people reading this didn’t make that assumption. But I’d lay down good money that many of the people who chose otherwise, consciously or unconsciously, specifically did so to subvert that expectation. They thought of the person in the wheelchair as someone who needed a caretaker first, then substituted another answer when they checked themselves. That assumption was a gut response, even if the reaction to it was also a gut response. It kind of sounds like I’m knocking them for that, and I’m not – that’s a good thing. It’s a good thing because the belief that disability makes everything about you less capable runs so deep it takes active effort to fight it off. It’s so omnipresent that it usually influences people legitimately trying to help, causing everything from talking loudly to deaf people to not offering promotions to disabled people because you think it would stress them out to this particular gem from the same source:

"Disabled We Stand” posted:

[A] woman had just climbed, on crutches, one of the longest staircases in the New York subway system and was standing at the top, getting her breath back, when some well meaning cavalier materialised out of the crowd, grabbed her up and carried her down to the bottom again. Had he bothered to ask if she needed assistance no problem would have arisen.

Not every player will come at KS with those assumptions still in place, but enough will that it needs to take a chisel to them and weaken that belief system enough to let things slip through. I mean, they absolutely could have just skipped this process, but it might fall afoul one of the most infuriating aspects of writing about minority issues: for someone with -isms in place, realistic depictions feel fake. The funny thing about preconceptions (which biases are a type of) is that they’re a lot more universal than people assume: at their heart, they’re tools that speed up cognition and reaction by fitting situations into patterns you already recognize on an instinctive level. If you see a number you don’t recognize calling you out of the blue, chances are you’ll assume they’re a telemarketer and not pick up. It could be anyone, it could be important, but you’re used to unexpected calls being telemarketers so you act on that assumption. They can even be helpful; if you see someone walk towards you in a dark alley reaching for something under their coat, you probably should get out of there. Your preconceptions make sense to you and form a basic part of your personality; they seem logical, even obvious. But biases are preconceptions that are wrong or harmful, and since they feel and work like any other preconception, you can’t tell the difference on the spot. Having your biases challenged can feel like a personal insult, given how deep in our heads biases can run, or it can feel like someone’s trying to put you in danger: if you react to a black person approaching you the same way you would a person in a dark alley, someone saying no, that’s kind of messed up sounds a hell of a lot like they want you to get mugged. And yeah, that’s an extreme example, but people make, say, economic decisions based on biases all the time, and if you tell them no, that’s kind of messed up they might react like you’re trying to scam them and lock down. Breaking down biases is an extremely delicate and difficult process that involves getting past a person’s defenses to avert that reaction. Without that process, you’ll more likely than not find efforts to broaden someone’s horizons just bounce off.

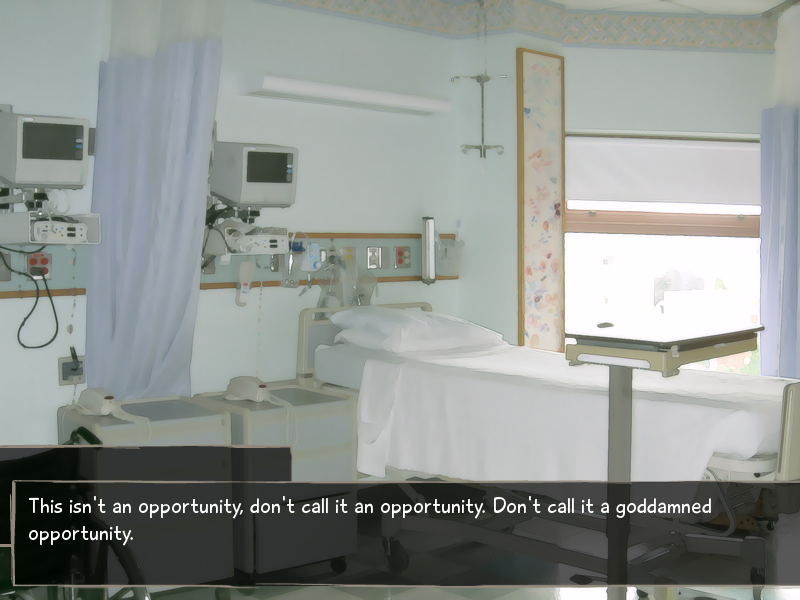

And that’s why Act 1 is Hisao Is Ableist Theater. Hisao rolls into Act 1 with his biases still intact and unchallenged, and, importantly, does not immediately change his ways. Here’s a screenshot I cut from the first update for space:

HISAO: “This isn’t an opportunity, don’t call it an opportunity. Don’t call it a goddamn opportunity.”

Nobody changes their opinion instantly. It doesn’t matter that Hisao is now disabled; he’s just as ableist as he’s ever been. Even if it’s a step up from staying in the hospital forever, to him, Yamaku is a school for people who are less than him. We see he’s willing to give his new classmates the benefit of the doubt and try to interact with them like normal people (and that’s not always the case), but… The ways he responds to his classmates – awkwardly dancing around topics, averting his eyes from people’s disabilities, wincing when he can’t – that’s all familiar, and obvious, to anyone who’s been on the receiving end. Those responses will make sense to many readers because they’re nearly universal, even to other disabled people; I know I’ve had to catch myself in the past. So the reader starts out in familiar territory.

And then they realize how anime the cast is. I’ve seen a couple people in the thread mention that it sticks out, and it’s true; the characters are all exaggerated and slightly unrealistic in a very specific way familiar to weeaboos everywhere. Hell, I could probably slap a -dere derivative on most of them if I was even lamer than I already am. We’re still in familiar territory. But it’s a different familiar territory. It’s one that doesn’t jive well with ableist biases but does jive well with the game’s portrayal of disability. When the average weeb filters through potential anime girlfriends and lands on the tsundere, they probably aren’t expecting her to need an interpreter just to talk to them; if they go for cheerful and/or athletic characters, they probably don’t anticipate their latest waifu using prosthetics so blatant she brings a clearly artificial running sound effect everywhere she goes. And yet nobody seems to agree that that’s weird. Every spotlighted student except Hisao has fully adapted to their disability; they are clearly aware of it and how it affects them, but it doesn’t dominate their lives the way some abled people assume disabilities do. They even display the blunt, blasé sense of humor about their disability that’s actually really common among real disabled people and which often shocks abled people. For someone familiar with disability, there is no cognitive dissonance there. For someone who isn’t, its lack itself causes cognitive dissonance. Just as Hisao gradually realizes his preconceptions are kind of bullshit by interacting with other characters, that friction between expectation and reality gradually breaks down readers’ preconceptions too.

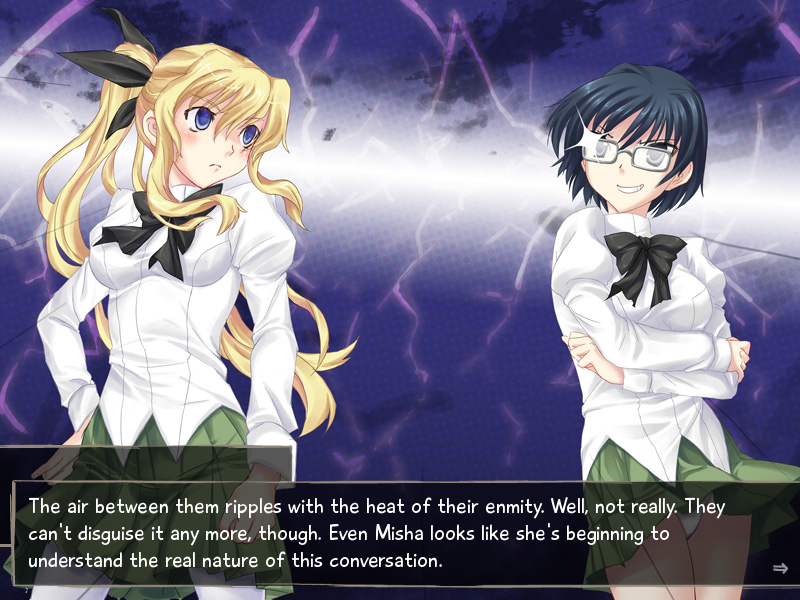

Let’s take a look at this process in action: Lilly and Shizune throwing down.

Most readers will immediately notice this scene features a blind girl facing off against a deaf girl. Many readers will also leap to the conclusion that their disabilities play a role in that rivalry. They kind of don’t, though. Shizune’s deafness is why Misha needs to be there to translate, and as the thread noted Lilly’s blindness is probably why she had to foist off filling out her forms on someone in her class (sidenote: her class includes people who have impaired eyesight like Kenji, so they can probably fill out those forms for her). But the dialogue makes it abundantly clear their clash has more to do with their conflicting personalities than anything else. Shizune is aggressive, harsh, and blunt, while Lilly’s comportment and passive-aggression reflect the ojou cliché her character’s clearly based on (forgive me, Father, for I have linked to TVTropes). For readers expecting their theoretically conflicting disabilities to dominate the scene, the fact that they barely come up puts them offkilter; for those expecting them to shape the conflict, they find that their expressions, stances, and dialogue play a much bigger role than their disabilities, which only come up in a utilitarian fashion. No judgment is offered by either one unless you interpret some of Shizune’s insults through that lens, and even then, they probably have more to do with her being a dick than judging Lilly’s disability. The process of breaking down biases is a gradual one: so far we’ve covered somewhere between 30,000 and 40,000 words in the updates, and that’s about half the length of an average novel in one part of Act 1 alone. But this and other scenes like it are designed to overwhelm bias with sheer weight of experience.

Eventually that friction wears biases down so far the reader’s mind starts to change. I want to draw attention to part of another scene:

Falconier111 posted:

Does getting used to this place mean that I'm giving up on being a normal person?

Or does it just mean that I'm becoming more understanding about those around me?

I'm distracted from my thoughts by the sight of Emi tearing into her lunch as if it had insulted her ancestors.

The presentation was pretty clunky and I probably could have portrayed it better, but I wanted to draw attention to this moment as one of the most important in the LP so far. Hisao’s been immersed in this environment for the better part of a week now. He’s spent time with half a dozen different people who have wildly divergent personalities but all feel little to no angst over their disabilities. Hell, earlier in this scene Emi’s like “they put me and Rin together so we could add up our limbs

”. He has this revelation, something kind of profound, in completely mundane circumstances next to Emi as she horfs down her food. This is the point where that cognitive friction finally wears Hisao down enough to open his mind. Earlier, his continual denial of his condition backfires during his run and nearly gives him a heart attack, forcing the Nurse and Mutou to spend time beating it into his head that he can’t avoid it anymore. Then, while he’s still recovering from that psychologically, he sits down with Emi and Rin, two very different people with very different personalities enjoying each other’s company and who cast his choices in stark relief: he can either deny his condition and have heart attacks, or accept it like they have and spend time with two people you can date. The choice is pretty obvious and drives the point home. It also complements a bit of quiet brilliance that I’m not sure the devs intended, though I really hope they did. You know how Emi’s route is both the easiest to stumble into and overwrites most other routes? Almost every first-time player not dedicated enough to beeline it for another character or using a guide will probably stumble into her route, get chewed out, and run into this scene. This lesson, the contrast between those two options, will be one of the first things the game drills into their head. Even if they realize they got Emi’s route and go back and restart the game, they’ve already been through those scenes and hopefully absorbed that point – and that will change the way they perceive the game and the characters.

”. He has this revelation, something kind of profound, in completely mundane circumstances next to Emi as she horfs down her food. This is the point where that cognitive friction finally wears Hisao down enough to open his mind. Earlier, his continual denial of his condition backfires during his run and nearly gives him a heart attack, forcing the Nurse and Mutou to spend time beating it into his head that he can’t avoid it anymore. Then, while he’s still recovering from that psychologically, he sits down with Emi and Rin, two very different people with very different personalities enjoying each other’s company and who cast his choices in stark relief: he can either deny his condition and have heart attacks, or accept it like they have and spend time with two people you can date. The choice is pretty obvious and drives the point home. It also complements a bit of quiet brilliance that I’m not sure the devs intended, though I really hope they did. You know how Emi’s route is both the easiest to stumble into and overwrites most other routes? Almost every first-time player not dedicated enough to beeline it for another character or using a guide will probably stumble into her route, get chewed out, and run into this scene. This lesson, the contrast between those two options, will be one of the first things the game drills into their head. Even if they realize they got Emi’s route and go back and restart the game, they’ve already been through those scenes and hopefully absorbed that point – and that will change the way they perceive the game and the characters.Of course, not everybody will get the hint. If you don’t absorb the lessons the game is trying to teach you, you’ll get the Bad Ending for Act 1. Every route, by the way, has at least a Good and Bad Ending, and sometimes a mediocre Neutral Ending. I will only ever cover the Good Endings because a) we are dealing with an insane amount of text already, I’m not adding like 40,000 more words at least to that count b) I need to leave SOMETHING for people to discover when they play the game themselves and c) I deal enough with disability-related unsolvable issues at work, I’m not piling more of that on myself unless I have to. However, each route will end with an analysis, and during that analysis I’ll talk about the Bad/Neutral Endings and what they mean in abstract. Once I finish a route, you can freely discuss all of its endings or any content in the route I skipped over or missed. Don’t even bother with spoiler tags; I’ll be dissecting them in the analysis anyway, so there’s no sense in hiding things. The only place this doesn’t apply is parts of Act 1 I haven’t been through or described. I recommend playing the game on your own so you can actually read those endings, but if you don’t care to or can’t for whatever reason, I’ll cover what happens and what it means.

Like so! If you manage to isolate yourself, insult others, or refuse to commit to any course of action, you’ll end up spending the school festival with Kenji on the roof of the school building, getting drunk with him at his “manly picnic”. You sink into nihilism, lose your balance, and fall off, dying. Yeah, I think this is the only way you can die in the game with one possible exception, but we’ll see when we get there. I hear a lot of players actually struggle with this, getting the Bad Ending by picking the options they’d take if they were in those situations. Fighting that impulse is the point. Well, mostly. I mean, let’s be honest, most of the people playing this game are awkward nerds who struggle to socialize anyway, so they may end up shoehorned into the manly picnic even if they otherwise wouldn’t make such obviously terrible decisions. The devs didn’t quite stick the landing on that one. What they were shooting for was Hisao combating his isolation. He was thrown into a situation different from anything he’d experienced before, even though parts of it were familiar. He could have kept his distance easily enough. But thematically, that parallels him denying his disability and disability in general, which is exactly what the game is trying to combat. Engaging with his new condition is equated to engaging with the people in his new school, and failing to reach out to them means failing to come to terms with his heart condition. And let’s be blunt, not doing so will kill him. Even if he didn’t die at the manly picnic, if he ignores his disability, eventually he’ll stumble into a situation his heart can’t cope with sooner rather than later. He might do that anyway even if he DOES start working with it, but denial will shorten his life. Refusing to accept responsibility for himself as he currently is, the sort of thing the first part of this post touched on, will backfire. That’s the message this part of the game is shooting for: you cannot ignore or dismiss disability. It doesn’t have to dominate your life, and in fact with some adjustment it won’t, but refusing to come to terms with it will only lead to tears. And that reflects on the player; in order to avoid the Bad Ending, they have to engage with the message of acceptance the game keeps bringing up.

If I had to pin down that message, I’d put it like this: you cannot approach disabilities from an ableist perspective, dehumanizing those who have them or denying its presence; you have to approach them realistically, as things that really do affect people but do not determine who they are or how they live outside of how those disabilities directly affect them. That’s a deep, nuanced perspective that even a decade later many activist groups have failed to grasp. The dominant agenda among most groups in the disability activism field, as it has been since before this game was released, mixes evoking pity with trying to prove our value to wider society. While that’s better than, like, eugenics, it’s quietly dehumanizing in its own way: instead of assuming that our lives have value because we are living human beings, it implies the most important thing about us is how we contribute to society and makes us objects of pity, worth less than fully functional humans because we have to prove our right to exist. That puts KS ahead of the game by an almost shocking margin. That is why I care about this game on a philosophical level. That’s why I said all the way back in the OP that it was one of the best representations of disability ever released to a wider audience. It takes an evenhanded, sensitive approach to our lives that very little else ever does, and I’ll never stop being grateful for that.

Of course, I also care about this game for its characters, which… Brings up a thorny topic. See, there’s a long-running debate in the community about the presumed sexlessness of disability, where abled people view disabled people as either so unattractive/dysfunctional that entering a relationship with them is a sacrifice or as objects of perverse lust. I have actually seen someone look at a person in a wheelchair, turn to their spouse, and say “wow, you’re so brave” to their faces. Hell, I had to step back and untangle my own feelings on the subject when I entered my first relationship. That sort of desexualization dehumanizes us further, cuts us off from other people, and quietly dovetails with eugenics (it makes sure we don’t reproduce), which, uh, yeah, that’s worth opposing. On the other hand, we are talking about sex, and even though the characters are all canonically 18 there’s still a creepo factor there. I originally planned on skipping this game’s sex scenes entirely in line with SA LP standard practice, but the more I think about it, the more I feel not addressing the sexlessness issue runs against the whole drive of this LP – it is, after all, skipping over a fundamental part of what it’s like to live as a disabled person because reading about it makes people uncomfortable. Which is a really blunt way of putting it, but it’s true. I want to poll the thread on how to handle this.

- Keep it pure. I won’t even note in the updates where sex scenes would show up, nor will I mention them in the route analyses. You could show this thread to your grandparents if it wouldn’t offend them for some other reason. I strongly recommend against this for the reason I listed above, but if the thread really wants it, I’ll bend.

- Keep it limited. Whenever a sex scene comes up, I’ll summarize it in a couple paragraphs and touch on what it means. I’ll bring them up in the analysis, too, but still only in how they reflect on the narrative.

- Keep it clear. I’ll lift the text directly out of the transcript and include it, spoilered and without pictures. Otherwise there wouldn’t be much of a difference from the second option.

Vote ends in 48 hours

Vote ends in 48 hours

I still have plenty more to say, but that can wait for after we start finishing routes. I’ll be looping back to parts of Act 1 every time we start a new one, but for now, it’s time we leave it behind and start running through Emi’s story.