Part 33: Bonus Update #3: Part 2 Postmortem

Bonus Update #3: Part 2 PostmortemThe Return of Bad Spiritual Allegory

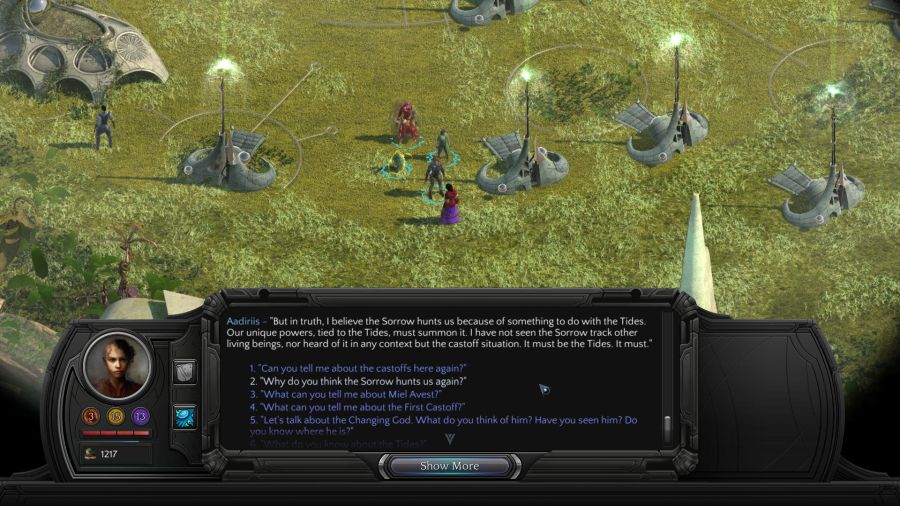

This is somewhat of a difficult post to write because the Valley of Dead Heroes section of this game is difficult to parse. A large part of the main quest is just standing around in Miel Avest listening to Aardiriis exposit at you about the Tides or the Endless Battle or whatever or going and talking to other castoffs at her direction. There's a large sidequest about going to not-Hell, but I don't believe that is actually necessary to complete the game. The game wants you to do it, but you could just go to Miel Avest, listen to Aardiriis ask you about trolleys, go on the fetch quest in the past, and discover that the Resonance Chamber is a trolley all without doing it. You're losing out on XP and loot, but you get to play less of this game and not read a ton of garbage dialogue, so whatever floats your boat.

I'm going to bring up my thesis again from the first postmortem. Tides of Numenera is trying to tell an intensely spiritual story about false gods and hubris while invoking a setting where literally every mystery was solved by men in the past. Either the story or the setting needed to be different, and this game was doomed at conception. Keep this in mind, because Part 2 veers abruptly into mysticism territory under the thick coating of trolleys.

The Inevitability of Death

Many of the sidequests in part 2 - and to a lesser extent the main quest - are about accepting that some day, you will die. The long Choi subplot is about helping Choi find peace in the not-afterlife. Inifere keeps the gates of hell open to avoid death at the hands of the Sorrow. Phoenix needs to be convinced that he needs to die again to find peace or whatever. It's not a coincidence that one of the first NPCs we meet after the cultist fight is Perseia, who is trying to get back into the Necropolis where her tomb is.

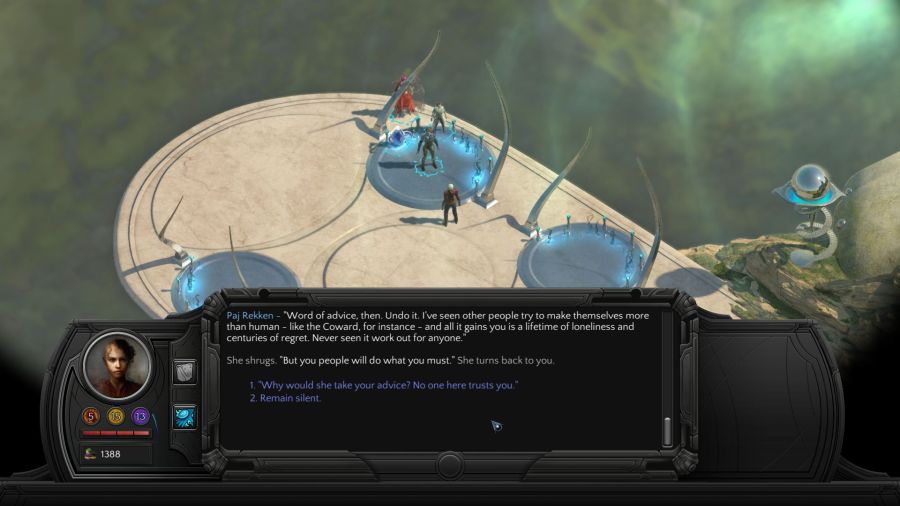

We get a lecture from Paj Rekken to Callistege warning her about following in the Changing God's footsteps and seeking immortality.

Lastly, of course, the Sorrow breaking into Miel Avest and slaughtering all of the centuries-old castoffs is reminiscent of the Red Death crashing Prince Prospero's ball and slaughtering all the nobles who thought they could hide from death and party forever.

Ultimately the Endless Battle and the Sorrow are both the direct result of the Changing God refusing to accept this fact and trying everything in his power to bring his daughter back to life.

This is, of course, completely undermined by other instances in the game, such as the immortal man who put himself into a sexbot in Caravanserai, or the techno-lich we freed from the tombs, or the fact that Phoenix can just...randomly decide he wants to come back to life, but ultimately the game is trying to come to terms with death. Why?

An Interview with Colin McComb posted:

ES: That's an interesting area to look into. Where does the "what does one life matter" question come from? Is it drawn from personal experiences?

CM: "A little bit, yeah. Now that I am older than I was when I was working on Planescape: Torment, I wanted to explore a little bit more the nature of mortality and about the marks we leave on life.

As one gets older, the question of your impending death becomes more pressing, I guess,

Anyway, from the interview we can tell that this game is at least partially about McComb grappling with a midlife crisis. I can't blame him for that. I can and will blame him, however, for the absolutely confusing and bizarre mishmash of imagery that got us here.

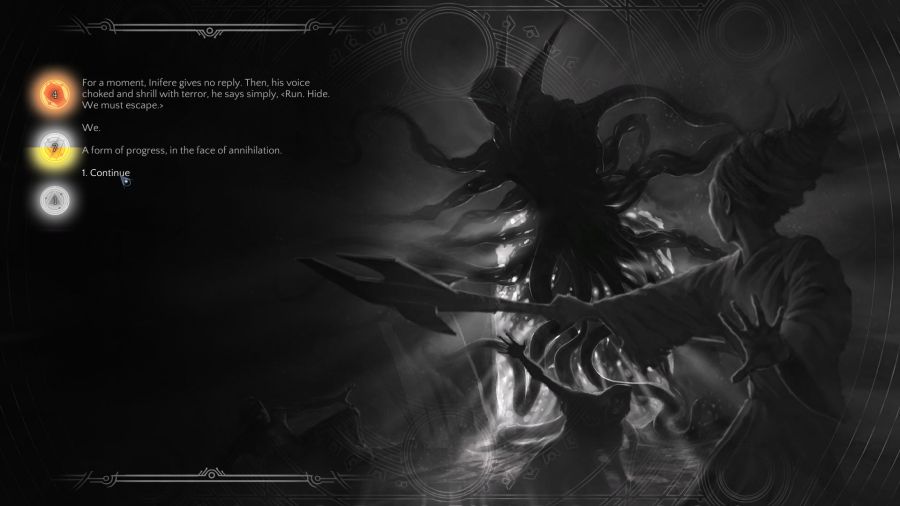

Start with the Sorrow. As a robed figure it calls to mind the Grim Reaper and the inexorable pursuit of death. This is solid. I enjoy ragging on the developers for their lack of originality, but I would be a lot more lenient if the game and marketing materials weren't constantly trying to convince me my mind should be blown and that everything in Numenera was super original because of science. Martin Luther King quotes John Bunyan, and Bunyan wrote a book where a character named "Help" helps the protagonist out of the literal "Mire of Despair". You don't need to be subtle to do an allegory. It helps, however, if you can actually keep consistent imagery and ideas to communicate what you are trying to do. Here the Grim Reaper design of the Sorrow has been diluted with the addition of tentacles, which is probably an allusion to H.P. Lovecraft and his tales of "cosmic horror." It's completely unnecessary and muddles the image. Lovecraft's great fear isn't a fear of death, it's a fear of loss of control that ties into his weird racist fears about sexy black women and his parents' being institutionalized at a young age. Lovecraft's gods are powerful, but ultimately have nothing to do with morality.

The Call of Cthulhu posted:

That cult would never die till the stars came right again, and the secret priests would take great Cthulhu from His tomb to revive His subjects and resume His rule of earth. The time would be easy to know, for then mankind would have become as the Great Old Ones; free and wild and beyond good and evil, with laws and morals thrown aside and all men shouting and killing and revelling in joy. Then the liberated Old Ones would teach them new ways to shout and kill and revel and enjoy themselves, and all the earth would flame with a holocaust of ecstasy and freedom. Meanwhile the cult, by appropriate rites, must keep alive the memory of those ancient ways and shadow forth the prophecy of their return.

We see this in the story, where Cthulhu rises and strikes down the sailors not because they have sinned, but because they are present and he is hungry.

The Sorrow - originally the Angel of Entropy - is literally just the Angel of Death sent to strike down the Changing God and his progeny for their sins.

Thus we don't actually need the extra mystery imposed by the clumsy mashon of Lovecraft! The Sorrow is mysterious because it represents death's inevitability, something many religious traditions posit is beyond human understanding and is only truly understood by the divine. By playing in God's toolbox by attempting to harness the Tides, the Changing God incurred the wrath of the gods for his hubris and is being struck down. The Sorrow isn't a pure force of nature like a hurricane or Godzilla which is dispassionately reacting because people fucked up and the nuclear reactor overloaded, there is a mind and a will greater than that of a mere human guiding it.

Here we see her visiting the sculptor who has progressed deeper into the divine mysteries, which the sculptor describes as "beautiful".

This is immediately tossed aside by the Miel Avest scene, which describes the Sorrow "shrieking in fury" and rather than describing it as cold and dark describes it as "roiling and nauseating". It's like a whole bunch of writers communicated by conference call and had different mental versions of what the Sorrow be - is it a divine messenger of death? An animalistic, berserk predator? We know it's not Lovecraft's cosmic horror that views humanity as beneath it because it only hunts castoffs and actually interacted with the sculptor - Yog-Sothoth wouldn't care - but it's visually coded as one and described using similar language in the Miel Avest segment. The fact that McComb and company renamed it explicitly to avoid religious connotations is especially baffling given the way they've characterized it.

Uh, what's a Tide?

This is an excellent question that needed to be asked more than two-thirds of the way through the game

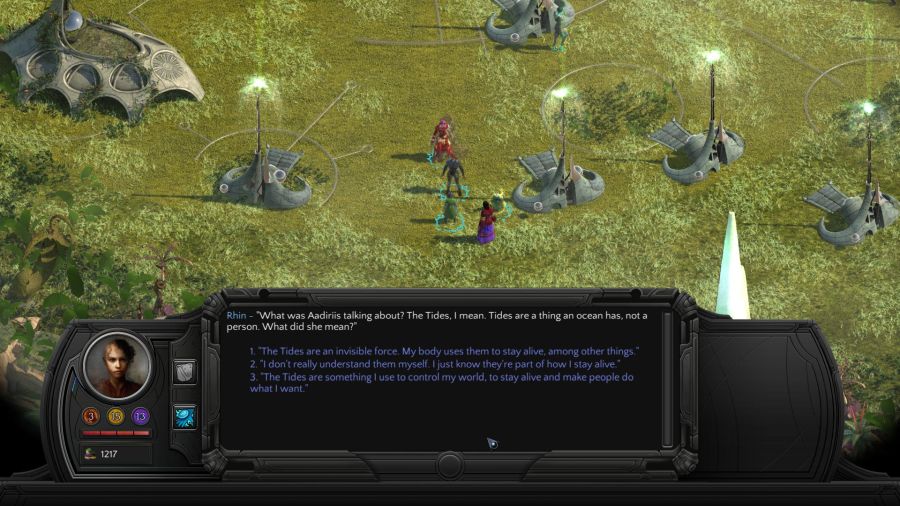

The Tides are a mystery that's supposedly central to this game - it's even named "Tides of Numenera" - and yet are treated as vaguely an afterthought. They are a power that can seemingly do anything from repairing rings to cursing people to controlling them (but not in combat!) to...whatever. The part of the game that none of the characters comment upon are that the Tides are continually watching us and judging our actions. If we start a fight, we get Red Tide. If we ask questions, we get Blue Tide.

Melnoth would have us believe the Tides are some kind of natural force, like gravity or magnetism, and the man has studied them for centuries and would know. Yet, gravity and magnetism don't judge what you're going to do with them, they're simply there. An electric current makes no moral judgement whether it's stopping a heart or starting a car. Even Oom, the creature that taught the Changing God himself about the Tides, barely refers to the individual Tides and always shows the five colors in dialogue rather than representing any as a whole.

This is because the Tides, like the D&D alignment system they're obviously based off of, represent divine law. Much like God/Odin/Osiris/whoever is watching to determine where you go in the afterlife, the Tides are watching you and judging your actions to be dealt with at some future date. Betray Rhin and the Gold Tide punishes you (eventually). Rant about how you desire power and that gets added to the ledger. It's exactly how in Dungeons and Dragons if you raise enough skeletons God hates you and you go to hell. Transgress against the Tides as the Changing God obviously did, and the Angel of Death comes to punish you for your sins.

Naturally the actual presentation of this game fucks everything up. First and foremost in all of this is Numenera's insistence that there is no spiritual significance to any of this and it's all just science you personally don't understand, but could theoretically be educated to do. Melnoth pointing out the Tides can be artificially induced is something that has no parallel with the laws of the gods - you obey the gods or get destroyed, not set up something with technobabble to maybe evade it.

The second is that this supposedly divine law is introduced not by a priest or man of faith, but by a slave master who uses it to dominate and enslave others. A generous soul could argue it's how religion is used to control others, but that form of religion is introduced by men and never backed by miracles like the Tides. It's an incoherent mess all around.

What Are We Actually Doing?

The end result of the clash between Numenera's truly scientific world and the Biblical hubris of the Changing God leads to a great incoherence that splashes into the plot. Multiple commentators in the thread have pointed out they have no idea what is going on in this game. A lot of these spiritual allegories have a spiritual striver as a protagonist, someone who is trying to discover how to live a good and virtuous life to honor their god(s) and gains wisdom along the way - but none of the stuff we've encountered has any kind of spiritual significance. The devil tempting us in the psychic bar isn't described as someone trying to get us to fall out of favor with God or become evil, it's just another flavor of alien with a sci-fi hivemind sheen. Descending into hell to rescue the souls of the damned is an act with no spiritual or metaphysical significance whatsoever. We have no stakes. Nominally we are under the looming threat of The Sorrow, but the Sorrow doesn't appear until act two with the exception of grinding in the optional mind dungeon. We have no incentive to change our behavior, something that tends to happen in these stories, and the end result is that we wander aimlessly through the generic sci-fi looking landscape arbitrarily passing judgment on people's lives. Ultimately, the desire to make a meaningful and deep experience is completely destroyed by McComb's insistence on sticking a square peg into a round hole and declaring victory now that the peg is kinda jammed in on its side.

We will see this come to its full inept conclusion in Act Three.