Part 23: January 10 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, we’ll be presenting a documentary on Nero, presented by Dr. Robertson. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twenty-second part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed the conquests of the Dutch across the Americas.

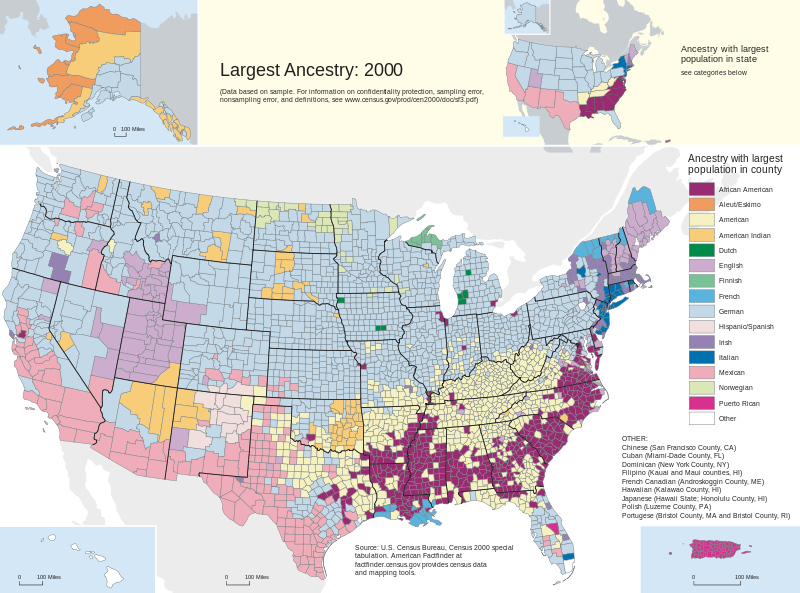

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twenty-second part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed the conquests of the Dutch across the Americas. Part of that conquest had led to a tremendous diversification of the people under the Dutch in the Americas. The Thirteen colonies had many people of many places, as had South America, the western plains of North America and the Iroquois further north were all distinct cultures and peoples. In Philadelphia and New Amsterdam, Dutch settlers were very common, attempting to achieve a more peaceful, quiet life away from the bustle of the great European cities. The British poor, especially the Irish had moved in great numbers to North America, especially New Amsterdam. The Scottish tended to move further North in modern day Canada, but the Scottish population of factory and plantation owners were also high in the Southern portions of North America. French fleeing from the Portuguese from around Montreal and those already in Louisiana and other southern regions, as well as Spanish across South America completed the diversification of Europeans in the Americas.

Part of that conquest had led to a tremendous diversification of the people under the Dutch in the Americas. The Thirteen colonies had many people of many places, as had South America, the western plains of North America and the Iroquois further north were all distinct cultures and peoples. In Philadelphia and New Amsterdam, Dutch settlers were very common, attempting to achieve a more peaceful, quiet life away from the bustle of the great European cities. The British poor, especially the Irish had moved in great numbers to North America, especially New Amsterdam. The Scottish tended to move further North in modern day Canada, but the Scottish population of factory and plantation owners were also high in the Southern portions of North America. French fleeing from the Portuguese from around Montreal and those already in Louisiana and other southern regions, as well as Spanish across South America completed the diversification of Europeans in the Americas.

Certain ethnicities tended to congregate around certain cities, mostly so they could form a unified community. Part of the community's purpose was to show solidarity against factory owners and Dutch ministers.

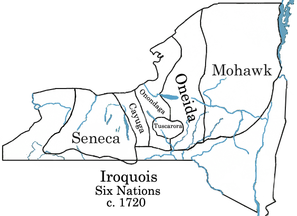

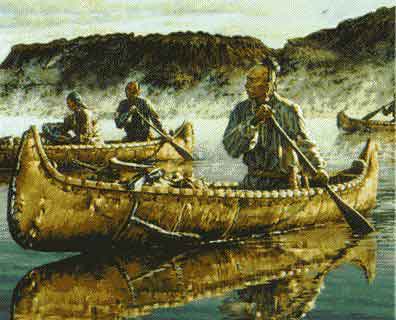

Dutch territory also controlled many tribes of Native Americans. The Iroquois confederacy remained intact to a degree after they were conquered by the Dutch, and the Cherokee though heavily policed by the Dutch had a semblance of independence until floods of European immigrants spread through their land, largely supplanting them by the mid to late 1800s. Each of these tribes had their own lands, policies, customs, religious leaders and enemies.

Dutch territory also controlled many tribes of Native Americans. The Iroquois confederacy remained intact to a degree after they were conquered by the Dutch, and the Cherokee though heavily policed by the Dutch had a semblance of independence until floods of European immigrants spread through their land, largely supplanting them by the mid to late 1800s. Each of these tribes had their own lands, policies, customs, religious leaders and enemies.

The natives nations were not completely unified nations. The tribes that the confederacy and nations were made up of had their own identity and culture.

This tremendous diversification made Dutch election laws very complex. Determining who had voting rights for which elections, what men had influence, and what priorities a politician required made navigating the Dutch political scene incredibly difficult. In America and India, the Dutch ministers hoping for election had to be a master of the many cultures they overlooked.

This tremendous diversification made Dutch election laws very complex. Determining who had voting rights for which elections, what men had influence, and what priorities a politician required made navigating the Dutch political scene incredibly difficult. In America and India, the Dutch ministers hoping for election had to be a master of the many cultures they overlooked. It was this vast gulf in local knowledge and custom that caused the political scene of the Dutch to break from their former two party system, and pushed them towards modern democracy. Previous elections had been between two powerful men, and whoever found it most expedient to support either or. Ministers often rallied behind one of the parties based more around whichever would further their career at the time, with several flip flopping between parties at a whim. However, with increasing need to solidify support and prove their worth, candidates for cabinet positions often found they had to consistently push party ideals to gain long term support from part of the voting base.

It was this vast gulf in local knowledge and custom that caused the political scene of the Dutch to break from their former two party system, and pushed them towards modern democracy. Previous elections had been between two powerful men, and whoever found it most expedient to support either or. Ministers often rallied behind one of the parties based more around whichever would further their career at the time, with several flip flopping between parties at a whim. However, with increasing need to solidify support and prove their worth, candidates for cabinet positions often found they had to consistently push party ideals to gain long term support from part of the voting base. This was what ultimately led to the fragmentation of the parties from the system of election between the Orange party and the Republicans. By 1750, the parties were the Orange party, which was popular in Amsterdam and the German states, the Republican party, which was popular in France and Spain, thus controlling the voting majority, the V.O.C. or Labour political party, which had support from India and America, and the Liberal party, which had moderate support amongst the educated elite and the Americans.

This was what ultimately led to the fragmentation of the parties from the system of election between the Orange party and the Republicans. By 1750, the parties were the Orange party, which was popular in Amsterdam and the German states, the Republican party, which was popular in France and Spain, thus controlling the voting majority, the V.O.C. or Labour political party, which had support from India and America, and the Liberal party, which had moderate support amongst the educated elite and the Americans.

The leader of the 1945 Labour party in the Netherlands. The V.O.C. Labour party was abolished near the end of the 18th century.

By region, the actual influence was not always direct. Technically, for the position as a minister other than the Statholder to be acquired in the United Provinces itself, one had to garner support only from citizens of Dutch origin, and further, only from Dutch citizens who were factory owners, business owners, nobles, land owners or wealthy merchants. In practice however, those men could only keep trade unions at bay by acquiescing to the demands of their workers. As many of those same factory or business owners operated abroad, the political demands placed upon them by their workers, and the lack of anonymous ballots meant many voting citizens were tremendously pressured to look out for local interests.

By region, the actual influence was not always direct. Technically, for the position as a minister other than the Statholder to be acquired in the United Provinces itself, one had to garner support only from citizens of Dutch origin, and further, only from Dutch citizens who were factory owners, business owners, nobles, land owners or wealthy merchants. In practice however, those men could only keep trade unions at bay by acquiescing to the demands of their workers. As many of those same factory or business owners operated abroad, the political demands placed upon them by their workers, and the lack of anonymous ballots meant many voting citizens were tremendously pressured to look out for local interests.

Workers picketing. A labour strike was one of the United Province's greatest financial fears, as in many regions, factory positions outnumbered the workforce. A side effect of government granted business licenses aimed at creating a larger voting pool.

In America, the sheer diversity of men was stabilized only by the very small number of voting men in the region. Factories were sparse, so labour demands were low. Instead, sailors and workers in the fish curing plants and fisheries were the greatest concentration of influence. These jobs giving better exposure to politics ended up drawing in great concentrations of relatively homogenous cultural groups. English citizens often became sailors or whalers, Irish and Spanish citizens often became dockhands and construction workers, Scots often worked in the few factories or plantations while the French, who were too far inland to contribute to those trades, became trappers in the fur trade. Of course, the main occupation of the majority of all immigrants was in farms and ranches.

In America, the sheer diversity of men was stabilized only by the very small number of voting men in the region. Factories were sparse, so labour demands were low. Instead, sailors and workers in the fish curing plants and fisheries were the greatest concentration of influence. These jobs giving better exposure to politics ended up drawing in great concentrations of relatively homogenous cultural groups. English citizens often became sailors or whalers, Irish and Spanish citizens often became dockhands and construction workers, Scots often worked in the few factories or plantations while the French, who were too far inland to contribute to those trades, became trappers in the fur trade. Of course, the main occupation of the majority of all immigrants was in farms and ranches.

A dockhand memorial in Dublin. Many of the immigrants from Ireland had years of experience in the trade, and so naturally gravitated to it. This pattern could be seen across many ethnic groups.

The natives, who were pushed further and further inland found their political influence dwindling every year, and their freedoms disappearing as the Europeans progressed further and further into their territories. These natives near Florida up through to Kentucky, the Cherokee were semi settled people, living in independent settlements and tribes. The Dutch often built factories near their settlements which the Cherokee did not wish to work within. It was easy to see why. The open fields, the cool mountains and the game filled forest were a utopia on earth compared to the smog filled, soot covered, rat infested factory cities.

The natives, who were pushed further and further inland found their political influence dwindling every year, and their freedoms disappearing as the Europeans progressed further and further into their territories. These natives near Florida up through to Kentucky, the Cherokee were semi settled people, living in independent settlements and tribes. The Dutch often built factories near their settlements which the Cherokee did not wish to work within. It was easy to see why. The open fields, the cool mountains and the game filled forest were a utopia on earth compared to the smog filled, soot covered, rat infested factory cities.

Factories were dangerous, dirty and crowded. Workers were lured to them by decent wages, and so they could live in closer proximity to the luxuries the city could provide, even for the working class. Cherokee, with their vast fields, hunting and moderate political freedom had no desire to work in these cities.

But without any ability to ensure that their voice was heard in the Hague, the native leaders needed to find some other means to preserve their way of life and their relative freedom. The Cherokee managed a semblance of this. Having received horses from the Spanish when they had first arrived in America hundreds of years ago, the Cherokee had taken to the horse and saddle very rapidly. The fertile fields of the mid west of North America was ideal for those horses, and many of the western settlers, even the simple towns folk, could own a powerful horse raised by the Cherokee. They preferred selling neutered males to decrease the odds of their customers raising their own horses.

But without any ability to ensure that their voice was heard in the Hague, the native leaders needed to find some other means to preserve their way of life and their relative freedom. The Cherokee managed a semblance of this. Having received horses from the Spanish when they had first arrived in America hundreds of years ago, the Cherokee had taken to the horse and saddle very rapidly. The fertile fields of the mid west of North America was ideal for those horses, and many of the western settlers, even the simple towns folk, could own a powerful horse raised by the Cherokee. They preferred selling neutered males to decrease the odds of their customers raising their own horses.

The Comanche, further west than the Cherokee. They had a stronger horse culture than the Cherokee, but were too far from the main Dutch outposts to compete economically. The Cherokee displaced them during the 1800s.

The Cherokee interests were primarily in keeping their lands free of the factories, the pollution and the settlers, and while they did eventually lose much of their land, huge swaths of fertile land were left to them as their homes, but more importantly, to raise thousands of horses. Many were sent back to Europe, and were steeds for French, German and Spanish cavalry in the 1800s. Others replaced the ox and mule in all but the poorest farmsteads and companies. Either way, the Cherokee had gained over a hundred years of relative security. It was only when the gas powered car and to a lesser degree the steam powered locomotive were invented that they lost much of their remaining lands.

The Cherokee interests were primarily in keeping their lands free of the factories, the pollution and the settlers, and while they did eventually lose much of their land, huge swaths of fertile land were left to them as their homes, but more importantly, to raise thousands of horses. Many were sent back to Europe, and were steeds for French, German and Spanish cavalry in the 1800s. Others replaced the ox and mule in all but the poorest farmsteads and companies. Either way, the Cherokee had gained over a hundred years of relative security. It was only when the gas powered car and to a lesser degree the steam powered locomotive were invented that they lost much of their remaining lands.

A horse drawn plow. In years prior, one would use a mule or an ox to draw a plow. A horse was often too expensive to be used as a farmer's beast of burden.

The Iroquois were in a less solid position. Thousands went into the fishing industry along the great lakes exporting thousands of pounds of cured trout to the rest of the Dutch Empire. This gave them some legitimacy and some voice to those natives, as several had opted to rely on the natives to supply them with fish. However, there were so few natives as compared to English and Dutch fishermen that the parties that had their interests in mind rarely won victories, or more often, their opinion was passed over completely with striking fishing towns simply being colonized by eager Europeans.

The Iroquois were in a less solid position. Thousands went into the fishing industry along the great lakes exporting thousands of pounds of cured trout to the rest of the Dutch Empire. This gave them some legitimacy and some voice to those natives, as several had opted to rely on the natives to supply them with fish. However, there were so few natives as compared to English and Dutch fishermen that the parties that had their interests in mind rarely won victories, or more often, their opinion was passed over completely with striking fishing towns simply being colonized by eager Europeans.

Fishing through the great lakes or St. Lawrence for salmon, which was then preserved, then sold to Dutch fisheries.

Their advantage in Dutch politics didn’t arise until the fall of the Cherokee in many respects. The Dutch had appealed to both to work in their factories as cheap labour, which the Cherokee had for the most part refused to do. The Iroquois on the other hand, had several hundred young men work in European factories, many of them disillusioned young native men, frustrated by the limitations of the Iroquois confederation in holding back the Dutch expansion into their lands. In a bit of propaganda and political spin, the Iroquois earned approximately the same rights as the men of India, taking control of several of the factories and plantations near or on their lands.

Their advantage in Dutch politics didn’t arise until the fall of the Cherokee in many respects. The Dutch had appealed to both to work in their factories as cheap labour, which the Cherokee had for the most part refused to do. The Iroquois on the other hand, had several hundred young men work in European factories, many of them disillusioned young native men, frustrated by the limitations of the Iroquois confederation in holding back the Dutch expansion into their lands. In a bit of propaganda and political spin, the Iroquois earned approximately the same rights as the men of India, taking control of several of the factories and plantations near or on their lands. So long as the Dutch received their taxes, they couldn’t care less if it was an Indian or a Native American running the factories, and by the late 1800s, the Iroquois had integrated into much of standard Dutch-American society. Only in the far west did they continue to live in their longhouses and farm their traditional rotation of squash, beans and corn. Whether this truly gave them freedom is debatable. Their culture was mostly forgotten, but they were financially independent far longer than the Cherokee were.

So long as the Dutch received their taxes, they couldn’t care less if it was an Indian or a Native American running the factories, and by the late 1800s, the Iroquois had integrated into much of standard Dutch-American society. Only in the far west did they continue to live in their longhouses and farm their traditional rotation of squash, beans and corn. Whether this truly gave them freedom is debatable. Their culture was mostly forgotten, but they were financially independent far longer than the Cherokee were.

The Dutch were able to build factories in Iroquois reservations, but the worker base had to be Iroquois. The Iroquois built some textile mills of their own as well.

Both cultures in the end, suffered greatly at the rapid expansion of European powers over their homelands. So long as the Dutch tax man was paid his dues, he didn’t care who occupied the land, and as the years wore on, it was clear that the natives were paying less than dense industrialized cities of immigrants would. In many cities today such as New York, the Iroquois population is essentially identical to the rest of the nation and that has been their life for the past hundred years. Even the limited towns that are considered Seneca or Cayuga are much the same as any modern American town.

Both cultures in the end, suffered greatly at the rapid expansion of European powers over their homelands. So long as the Dutch tax man was paid his dues, he didn’t care who occupied the land, and as the years wore on, it was clear that the natives were paying less than dense industrialized cities of immigrants would. In many cities today such as New York, the Iroquois population is essentially identical to the rest of the nation and that has been their life for the past hundred years. Even the limited towns that are considered Seneca or Cayuga are much the same as any modern American town.

The modernization of the Iroquois economy had its roots in the modern Dutch styled towns built in the 1700s.

They weren’t the only minority in the Americas that were trying to pull influence from Europe though. Massive organized work strikes amongst Irish and English workers in the fisheries and trade ports, be it the dockhands or the sailors was an omnipresent threat. While there were many excellent Dutch sailors as well, many of them preferred working in the East Indian theater, where the much more lucrative spice trade guaranteed better wages. Sailors of the Americas were often of English descent, many being the children of pirates that had fled Britain, or British colonists of the former 13 colonies. Trading in cotton for the voracious European factories, shipping cheap staple foods, and fishing Atlantic cod, their wages were not as high as their East Indian equivalents.

They weren’t the only minority in the Americas that were trying to pull influence from Europe though. Massive organized work strikes amongst Irish and English workers in the fisheries and trade ports, be it the dockhands or the sailors was an omnipresent threat. While there were many excellent Dutch sailors as well, many of them preferred working in the East Indian theater, where the much more lucrative spice trade guaranteed better wages. Sailors of the Americas were often of English descent, many being the children of pirates that had fled Britain, or British colonists of the former 13 colonies. Trading in cotton for the voracious European factories, shipping cheap staple foods, and fishing Atlantic cod, their wages were not as high as their East Indian equivalents.

Dutch in V.O.C. controlled India lived as though they were wealthy Dukes. Their American counterparts were far more humble.

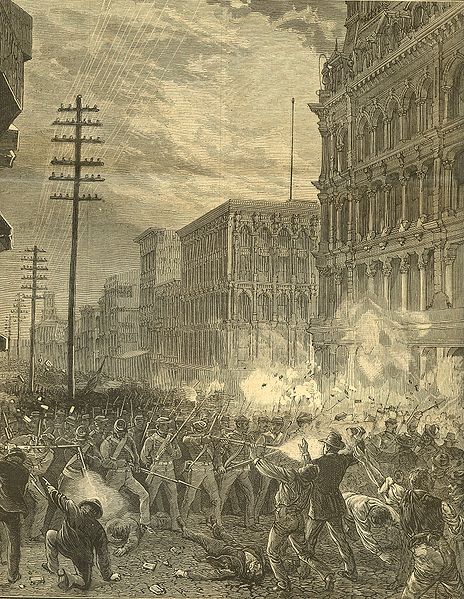

English and Irish threats of forming trade unions required near constant policing, bribery and at times even military intervention, but in the end, as the English and Irish could easily paralyze the Dutch trade causing starvations in port cities and the complete loss of income in hundreds of cotton factories across their empire, they wielded tremendous political power. Twice, the Dutch government attempted to bring in other labourers to supplant them, but found notable dips in income as less experienced crews were either late on deliveries by months, or fell prey to British privateers. What was worse, union leaders were just as capable of bribery, murder and coercion as the government. Many people slowly drew away from those occupations for fear of the English or Irish raiding their homes and terrorizing their families. As effective as Dutch policing was at suppressing general rebellion, they were less skilled at denying labour unions, as that was theoretically the responsibility of the business owners.

English and Irish threats of forming trade unions required near constant policing, bribery and at times even military intervention, but in the end, as the English and Irish could easily paralyze the Dutch trade causing starvations in port cities and the complete loss of income in hundreds of cotton factories across their empire, they wielded tremendous political power. Twice, the Dutch government attempted to bring in other labourers to supplant them, but found notable dips in income as less experienced crews were either late on deliveries by months, or fell prey to British privateers. What was worse, union leaders were just as capable of bribery, murder and coercion as the government. Many people slowly drew away from those occupations for fear of the English or Irish raiding their homes and terrorizing their families. As effective as Dutch policing was at suppressing general rebellion, they were less skilled at denying labour unions, as that was theoretically the responsibility of the business owners.

Military actions in putting down labour disputes often fixed little, disrupted production even further, and fomented unrest. The Dutch preferred enforcing better wages for workers by law.

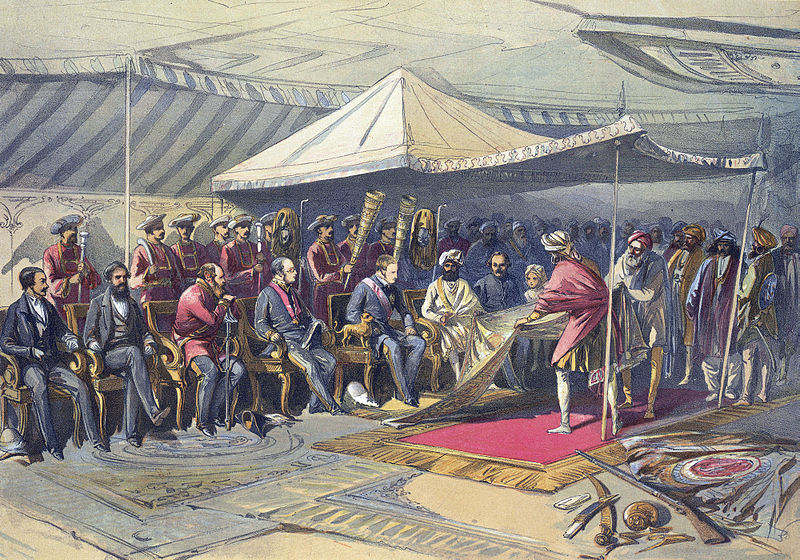

In India, the general populace was far more persuasive. It was essentially impossible for Europeans to move to India to replace the local populace as labourers, meaning the only labour the Dutch could get were the natives. Referred to as “dominions” rather than colonies, the Indians managed to attain a similar state of independence as the French and Spanish. However, each President within India was directly answerable to the Dutch in Amsterdam, meaning they were more directly controlled by the Dutch, or more visibly controlled by the Dutch.

In India, the general populace was far more persuasive. It was essentially impossible for Europeans to move to India to replace the local populace as labourers, meaning the only labour the Dutch could get were the natives. Referred to as “dominions” rather than colonies, the Indians managed to attain a similar state of independence as the French and Spanish. However, each President within India was directly answerable to the Dutch in Amsterdam, meaning they were more directly controlled by the Dutch, or more visibly controlled by the Dutch.

European ministers meeting with Indian rulers. While in control of their nation at face value, the Dutch were the ones ultimately in control.

This meant politicians around India needed to consider both support for local presidents and ministers, but had a more direct stake in trying to influence the cabinet in Amsterdam. While they were capable of voting for the Statholder, the remaining ministers, and particularly the justice and financial ministers were harder to influence. Doubly so, as many of the factory owners in India were Indians, meaning they could not participate in the vote for the Dutch cabinet. Their only means of influencing the Dutch financial and Justice minsters was through the V.O.C.

This meant politicians around India needed to consider both support for local presidents and ministers, but had a more direct stake in trying to influence the cabinet in Amsterdam. While they were capable of voting for the Statholder, the remaining ministers, and particularly the justice and financial ministers were harder to influence. Doubly so, as many of the factory owners in India were Indians, meaning they could not participate in the vote for the Dutch cabinet. Their only means of influencing the Dutch financial and Justice minsters was through the V.O.C. The V.O.C. by default wanted to ensure the maintenance and financing of the Indian sub-continent, as well as policies to placate much of the populace. They did not wish to spend money in policing them, doubly after the evacuation in the 1740s and they relied heavily on the industry of India for profits. As such, the Indian factory owners and the political V.O.C. party were heavily influential on one another and highly reliant on one another. With fewer opportunities, education and fierce competition for jobs in India, the average Indian labourer held very little power. Power and wealth in India concentrated higher and higher to the wealthy land owners until Indian independence in the 1900s.

The V.O.C. by default wanted to ensure the maintenance and financing of the Indian sub-continent, as well as policies to placate much of the populace. They did not wish to spend money in policing them, doubly after the evacuation in the 1740s and they relied heavily on the industry of India for profits. As such, the Indian factory owners and the political V.O.C. party were heavily influential on one another and highly reliant on one another. With fewer opportunities, education and fierce competition for jobs in India, the average Indian labourer held very little power. Power and wealth in India concentrated higher and higher to the wealthy land owners until Indian independence in the 1900s. The V.O.C. party became the official opposition to the Republican party by 1756, surpassing the Orange party in votes. Amsterdam, worried that their own interests were starting to fall by the wayside were shocked. Though the greatest concentration of wealth and the wealthy were still focused in Amsterdam and the Hague, the Dutch saw hundreds of millions of guilders moving into France, Germany, India, Spain. The elite of Amsterdam were content now, but with investment money being put out to all corners of their Empire to fund German, French, Spanish, Indian farms and factories rather than their own, many felt they were bankrupting themselves.

The V.O.C. party became the official opposition to the Republican party by 1756, surpassing the Orange party in votes. Amsterdam, worried that their own interests were starting to fall by the wayside were shocked. Though the greatest concentration of wealth and the wealthy were still focused in Amsterdam and the Hague, the Dutch saw hundreds of millions of guilders moving into France, Germany, India, Spain. The elite of Amsterdam were content now, but with investment money being put out to all corners of their Empire to fund German, French, Spanish, Indian farms and factories rather than their own, many felt they were bankrupting themselves. This feeling of disquiet in Amsterdam would linger among their populace, and ironically, in many academies and coffee shops in the United Provinces there is talk about cutting the rest of the Western Atlantic Federation off, keeping their tremendous trade profits for themselves. With the size and complexity of their trade empire, the loss of tax revenue, after the consideration of costs and expansion abroad meant the Dutch would keep far more for themselves.

This feeling of disquiet in Amsterdam would linger among their populace, and ironically, in many academies and coffee shops in the United Provinces there is talk about cutting the rest of the Western Atlantic Federation off, keeping their tremendous trade profits for themselves. With the size and complexity of their trade empire, the loss of tax revenue, after the consideration of costs and expansion abroad meant the Dutch would keep far more for themselves. The government however, continued their expansion across the Empire, hoping to appease the peoples within their cities. Greater and greater demands are met leaving armies only along their frontier while factory owners and politics were left to police their interior holdings. They do this through investment, payment to business, increasing wages, and catering to the burgeoning middle class, relying on brute force only when absolutely necessary.

The government however, continued their expansion across the Empire, hoping to appease the peoples within their cities. Greater and greater demands are met leaving armies only along their frontier while factory owners and politics were left to police their interior holdings. They do this through investment, payment to business, increasing wages, and catering to the burgeoning middle class, relying on brute force only when absolutely necessary. This was the United Provinces in the mid 1700s. Their enemies were still abroad, be they in America, the British isles, or looming over their borders in Germany. So great however, was Dutch military power that those threats were not anywhere near so ominous as themselves. Each component of the Dutch Empire had their own wants, needs, and each was held tightly by the Dutch ministers. The threat to the entire Empire by then was that it far more likely to fall apart internally than from any external pressure.

This was the United Provinces in the mid 1700s. Their enemies were still abroad, be they in America, the British isles, or looming over their borders in Germany. So great however, was Dutch military power that those threats were not anywhere near so ominous as themselves. Each component of the Dutch Empire had their own wants, needs, and each was held tightly by the Dutch ministers. The threat to the entire Empire by then was that it far more likely to fall apart internally than from any external pressure.To those of you interested in this program, please check out BBC channel four on television. We'll be doing a short series of videos on the making of these documentaries.

Next Dr. Robertson will be doing a presentation on Nero of Rome. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.