Part 24: January 13 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, Professor Douglas will be presenting a documentary on the history of roads. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twenty-fourth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed the increased diversity of ethnicities within the Dutch Empire, and the influence they had over the politics of the Empire.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twenty-fourth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed the increased diversity of ethnicities within the Dutch Empire, and the influence they had over the politics of the Empire. Back into the action, the Dutch continued their push through North America. Their fleet was sent from the channel and the Mediterranean to contest and rout out the strong British fleet from North America, hoping to clear the way for the Dutch armies to return to Europe, they hoped to smash them in time to get their armies back home safely.

Back into the action, the Dutch continued their push through North America. Their fleet was sent from the channel and the Mediterranean to contest and rout out the strong British fleet from North America, hoping to clear the way for the Dutch armies to return to Europe, they hoped to smash them in time to get their armies back home safely.

The Dutch armies in North America, thanks to the presence of the Portuguese North of the British were in a clear position to beat the British and push them off the continent. This meant the veterans would be returning to Europe soon, though many retired to live as colonists.

The British fleet had set to raiding and burning down Dutch ports across the American theater causing tremendous economic damage. With the British navy tied down in America, the fleet in India was safe to set sail home around South Africa, and all the way North back up to Spain, then up into the British isles. The army that would soon be free from the American campaign however, would not make it across the Atlantic with the British fleet hounding them. With limited fleets in both Britain and Amsterdam ready for small scale naval warfare if necessary, and a small number of first rate ships of the line being produced in Le Havre, the Dutch determined it worth the risk dispatching their fleet to the Atlantic.

The British fleet had set to raiding and burning down Dutch ports across the American theater causing tremendous economic damage. With the British navy tied down in America, the fleet in India was safe to set sail home around South Africa, and all the way North back up to Spain, then up into the British isles. The army that would soon be free from the American campaign however, would not make it across the Atlantic with the British fleet hounding them. With limited fleets in both Britain and Amsterdam ready for small scale naval warfare if necessary, and a small number of first rate ships of the line being produced in Le Havre, the Dutch determined it worth the risk dispatching their fleet to the Atlantic.

The British navy traveled from Dutch port to Dutch port. Undefended against such a large navy, the Dutch ports were sacked for powder and supplies, disrupting trade and forcing the Dutch to spend millions in repairs.

Arriving early in 1745 around the coast of British controlled Newfoundland, the Dutch fleet swept south towards the British fleet. British trade ships, able to move quickly around the region managed to warn the British who intercepted them off the coast of Hispanola by November 1745.

Arriving early in 1745 around the coast of British controlled Newfoundland, the Dutch fleet swept south towards the British fleet. British trade ships, able to move quickly around the region managed to warn the British who intercepted them off the coast of Hispanola by November 1745.

The British managed to gain the initiative against the Dutch fleet. They followed new from their own trade ships and from captured Dutch fishing and whaling ships.

Both the British and Dutch navies had been a decade old, and in either case, the ships used were not the newest or most powerful they could gain access to. The Dutch were already producing their newer first rate ships of the line, but could have deployed a second rate if they had spent more on expanding their navy. The British likewise could have deployed third or second rate ships, but had considered it infeasible with Portsmouth blockaded, preventing any new ships from joining their fleet. With the Dutch absent, new ships were put into production to block the Dutch at the channel.

Both the British and Dutch navies had been a decade old, and in either case, the ships used were not the newest or most powerful they could gain access to. The Dutch were already producing their newer first rate ships of the line, but could have deployed a second rate if they had spent more on expanding their navy. The British likewise could have deployed third or second rate ships, but had considered it infeasible with Portsmouth blockaded, preventing any new ships from joining their fleet. With the Dutch absent, new ships were put into production to block the Dutch at the channel.

The Grand Docks of Le Havre, by Monet. The grand docks were the primary Dutch military port where the Statholder commissioned the production of French ships which were then sold to the Dutch.

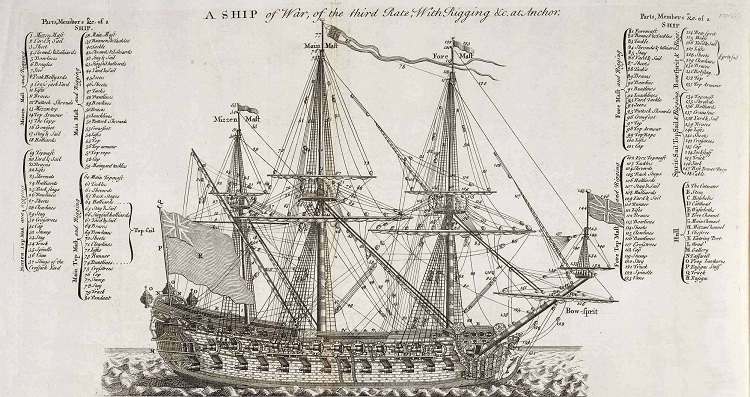

The Dutch navy did have a few advantages however. While it had failed to produce any second rate ships of the line, they were the first to produce third rate ships of the line. With over twenty more guns than a fourth, and a much sturdier hull, a third rate ship was considered one of the best ships to captain in the age. Fast, heavily armed and surprisingly maneuverable, a third rate was considered an excellent all around ship, and was easily more than a match for a fourth rate. Three such ships had been put into production and were sent to North America by the Dutch. Their Mediterranean fleet also contributed a pair of bomb ketches, ships with long range indirect fire support which could soften up ships as they advanced, or if the Dutch were lucky, ignite them from long range.

The Dutch navy did have a few advantages however. While it had failed to produce any second rate ships of the line, they were the first to produce third rate ships of the line. With over twenty more guns than a fourth, and a much sturdier hull, a third rate ship was considered one of the best ships to captain in the age. Fast, heavily armed and surprisingly maneuverable, a third rate was considered an excellent all around ship, and was easily more than a match for a fourth rate. Three such ships had been put into production and were sent to North America by the Dutch. Their Mediterranean fleet also contributed a pair of bomb ketches, ships with long range indirect fire support which could soften up ships as they advanced, or if the Dutch were lucky, ignite them from long range.

Details of a third rate. They were widely considered the most useful ship of the age of sail, being both economical, fast, powerful and durable. While a first rate was more prestigious, they were inordinately expensive to maintain in service and were often unneeded except in the largest set piece battles.

The British on the other hand, had a superior Admiral leading a larger navy. With more fourth rates than the Dutch had thirds, and a great deal more fifths than the Dutch, as well as several support vessels, the British were not lacking in cannons.

The British on the other hand, had a superior Admiral leading a larger navy. With more fourth rates than the Dutch had thirds, and a great deal more fifths than the Dutch, as well as several support vessels, the British were not lacking in cannons.

The Ariadne, a British fourth rate. Weaker than the third rates, Britain had opted for the fourth rates due to cost, whereas the Dutch had near limitless funds when they needed them.

That Admiral was John Leake, grandson of the Admiral of the same name who fought at Beachy Head alongside the Dutch. By now, Leake had grown to be a fine admiral in his own right. His father, who was not favoured by parliament and had few friends in the Lord Admirality by the time of his death had left his son few prospects, but he had been a renowned admiral for the age, and with the threat of Dutch invasion persistently looming, an iconic admiral was what the British had thought they needed.

That Admiral was John Leake, grandson of the Admiral of the same name who fought at Beachy Head alongside the Dutch. By now, Leake had grown to be a fine admiral in his own right. His father, who was not favoured by parliament and had few friends in the Lord Admirality by the time of his death had left his son few prospects, but he had been a renowned admiral for the age, and with the threat of Dutch invasion persistently looming, an iconic admiral was what the British had thought they needed.

John Leake the older. A renowned admiral and a politician, he retired from office after political change put his allies away from the center stage.

Despite his familial connections, John Leake the younger was an inordinate hard worker. Fighting his way through the ranks to make up for his father’s middling career, and his grandfather’s lack of influence later on in his life, he had to distinguish himself every step of the way. His commission, the 48 gun frigate Achilles was no match for the Dutch ships of the line, or even his own fourth rates under his command, but John Leake had won his fame as the captain of the Achilles combating the Swiss around the English channel, driving away the weak Prussian fleet pirating their trade, and in hounding Dutch trade ships across the world. While he had yet to win a decisive set piece battle, Leake was the most experienced and qualified man to lead the British Navy. With the fleet he had, he opted to remain aboard the Achilles for both sentimental reasons, and because it had become an iconic ship. Remaining in the Achilles rather than taking a fourth rate would be better for the morale of the fleet.

Despite his familial connections, John Leake the younger was an inordinate hard worker. Fighting his way through the ranks to make up for his father’s middling career, and his grandfather’s lack of influence later on in his life, he had to distinguish himself every step of the way. His commission, the 48 gun frigate Achilles was no match for the Dutch ships of the line, or even his own fourth rates under his command, but John Leake had won his fame as the captain of the Achilles combating the Swiss around the English channel, driving away the weak Prussian fleet pirating their trade, and in hounding Dutch trade ships across the world. While he had yet to win a decisive set piece battle, Leake was the most experienced and qualified man to lead the British Navy. With the fleet he had, he opted to remain aboard the Achilles for both sentimental reasons, and because it had become an iconic ship. Remaining in the Achilles rather than taking a fourth rate would be better for the morale of the fleet.

The Achilles cleared for action with Admiral John Leake.

Against him was Gerard van Curen, a vastly different officer. His family had no particular experience in the Navy, and he had only enlisted as an officer to avoid inheriting his father’s rapidly failing factory. Getting in while he could still qualify, and afford the expenses of being an officer. Once he was a lieutenant stationed in the Mediterranean, he had been aboard the Ter Goes when it won its seminal battle against the Austrian flotilla in their battle along the Barbary coast. From there, he was returned to Amsterdam and placed as the first lieutenant aboard the Wapen van Holland in the channel, where he had committed to very little action in some time. Eventually granted his own commission of the Spartiate after the previous captain retired, he spent another few years once again doing very little.

Against him was Gerard van Curen, a vastly different officer. His family had no particular experience in the Navy, and he had only enlisted as an officer to avoid inheriting his father’s rapidly failing factory. Getting in while he could still qualify, and afford the expenses of being an officer. Once he was a lieutenant stationed in the Mediterranean, he had been aboard the Ter Goes when it won its seminal battle against the Austrian flotilla in their battle along the Barbary coast. From there, he was returned to Amsterdam and placed as the first lieutenant aboard the Wapen van Holland in the channel, where he had committed to very little action in some time. Eventually granted his own commission of the Spartiate after the previous captain retired, he spent another few years once again doing very little.

The Spartiate wasn't actually a Dutch vessel, nor was it purchased by the Dutch. It had been captured by the Dutch from the French in 1702. It was the vessel of Admiral Chateau-Renault.

His commission of the prestigious third rate ship, the Westfriesland was one of both luck and circumstance. Every Dutch officer knew that they were constructing a set of one hundred gun first rate ships at Le Havre, due to be complete in a year and every captain wanted to earn one of them as their commission. That was something unlikely to fall in their hands if they were already leading a fleet from the Westfriesland. This meant it was the more junior captains such as Curen that had lobbied to attain the third rate. Being the most experienced of those captains, he had managed to barely eke out command of the powerful vessel.

His commission of the prestigious third rate ship, the Westfriesland was one of both luck and circumstance. Every Dutch officer knew that they were constructing a set of one hundred gun first rate ships at Le Havre, due to be complete in a year and every captain wanted to earn one of them as their commission. That was something unlikely to fall in their hands if they were already leading a fleet from the Westfriesland. This meant it was the more junior captains such as Curen that had lobbied to attain the third rate. Being the most experienced of those captains, he had managed to barely eke out command of the powerful vessel.

The first third rate produced by the Dutch and possibly the first produced in the world. The Westfriesland had 72 guns over two gun decks, a sturdy hull and a massive crew.

Command of the Westfriesland came with an additional responsibility. Curen was made acting admiral until the completion of their first rate ships, and with that, his first job was to be on preparation for an engagement against the British in North America, which would see him set into action to the North American theater. The relatively inexperienced officer was well out of his league against Leake, but was certainly leading the superior vessels, and the Dutch had hoped, superior fleet.

Command of the Westfriesland came with an additional responsibility. Curen was made acting admiral until the completion of their first rate ships, and with that, his first job was to be on preparation for an engagement against the British in North America, which would see him set into action to the North American theater. The relatively inexperienced officer was well out of his league against Leake, but was certainly leading the superior vessels, and the Dutch had hoped, superior fleet. As the British had managed to take the offensive approach, the Dutch were left sailing into the wind to come to grips with the British fleet meaning their ships would take longer to turn to line to concentrate their fire on the British ships as they lined up to take their shots. To counter this, the Dutch arranged their ships into two separate lines of battle. Their faster ships were placed on the outside line, with the inner line turning in towards them, forming a single line at the outer turning point. Their heavier line consisted of their slowest ships, the captured Spanish Galleons, and the Dutch third rate ships. This meant that the Westfriesland would end up in the middle of the Dutch line, even if they were one of the first ships to contact the British. Fortunately, this would give Curen a solid position to order his fleet. In between the lines, such that the converging lines formed a barrier around them, were the indirect firing bomb ketch, which would rain down ordinance over the British line as it passed.

As the British had managed to take the offensive approach, the Dutch were left sailing into the wind to come to grips with the British fleet meaning their ships would take longer to turn to line to concentrate their fire on the British ships as they lined up to take their shots. To counter this, the Dutch arranged their ships into two separate lines of battle. Their faster ships were placed on the outside line, with the inner line turning in towards them, forming a single line at the outer turning point. Their heavier line consisted of their slowest ships, the captured Spanish Galleons, and the Dutch third rate ships. This meant that the Westfriesland would end up in the middle of the Dutch line, even if they were one of the first ships to contact the British. Fortunately, this would give Curen a solid position to order his fleet. In between the lines, such that the converging lines formed a barrier around them, were the indirect firing bomb ketch, which would rain down ordinance over the British line as it passed.

The Dutch approaching the British. The faster ships are on the right of the picture, the bomb ketch were being encircled in the middle, and the heavier ships were on the left of the picture. The heavy line was hoping to turn into the back of the light line to complete a straight line.

The British deployed similarly, their faster ships on their right, their slower ships on their left. The British had the wind, and so would not have as much trouble turning. Instead, the faster ships would match the Dutch line at full sprint, and their slower vessels would engage the rear of the Dutch heavy formation before it could pull into line. This put the Achilles somewhat to the fore, but not as the lead vessel which the British expected would be destroyed rapidly. The British, which outnumbered the Dutch would then use their longer and faster tailing ships to attempt to overwhelm the Dutch back lines in a general brawl.

The British deployed similarly, their faster ships on their right, their slower ships on their left. The British had the wind, and so would not have as much trouble turning. Instead, the faster ships would match the Dutch line at full sprint, and their slower vessels would engage the rear of the Dutch heavy formation before it could pull into line. This put the Achilles somewhat to the fore, but not as the lead vessel which the British expected would be destroyed rapidly. The British, which outnumbered the Dutch would then use their longer and faster tailing ships to attempt to overwhelm the Dutch back lines in a general brawl.

The British were similarly deployed into two lines. In their case, they would not need to turn as sharply, and so the faster vessels simply overtook the slower line. A much simpler and more reliable means of lengthening a line from two parallel lines.

Both fleets managed to approach as they wanted, the bomb ketches firing into the British lead ships with little effect, but disabling many light cannons over the top decks of their ships as they passed. The fast Dutch and British frigates managed to arrange into a line at the fore, exchanging volleys. However, the Dutch third rates managed to slowly turn into the battle before the second British line could catch up, and while disjointed from their forward line, they were capable of sending crippling volleys into the British ships.

Both fleets managed to approach as they wanted, the bomb ketches firing into the British lead ships with little effect, but disabling many light cannons over the top decks of their ships as they passed. The fast Dutch and British frigates managed to arrange into a line at the fore, exchanging volleys. However, the Dutch third rates managed to slowly turn into the battle before the second British line could catch up, and while disjointed from their forward line, they were capable of sending crippling volleys into the British ships.

Third rates cutting in across the lighter British ships. The third rate's volleys were absolutely devastating to the smaller frigates.

The British were clearly outmatched in their first pass, but even before the Dutch third rates had arranged themselves into a functional line, the British first line had passed by, the second crossing in front of the Dutch galleons. After the first sets of volleys, they British also held the advantage at the fore, as the Dutch sixth rate and fluyt fifth rate frigates were being outmatched by the British fifth rates.

The British were clearly outmatched in their first pass, but even before the Dutch third rates had arranged themselves into a functional line, the British first line had passed by, the second crossing in front of the Dutch galleons. After the first sets of volleys, they British also held the advantage at the fore, as the Dutch sixth rate and fluyt fifth rate frigates were being outmatched by the British fifth rates. By the end of the first Dutch pass, the British second line broke to port encircling the back line of Dutch ships, and bringing the Dutch bomb ketch into range. One was blown apart while the other was driven out of the battle.

By the end of the first Dutch pass, the British second line broke to port encircling the back line of Dutch ships, and bringing the Dutch bomb ketch into range. One was blown apart while the other was driven out of the battle.

The British cut and surround the Dutch back lines, blowing apart a bomb ketch.

The Dutch were forced to turn their third rates back around to manage the British fourth rate ships of the line, as well as their long line of supporting vessels. The British fore was heavily battered, but left with enough guns to force the Dutch light line out of the fight. As the Dutch ships had come about, they had brought their guns across the fore and aft of the two British lines which forced the British light line out of the fight as well.

The Dutch were forced to turn their third rates back around to manage the British fourth rate ships of the line, as well as their long line of supporting vessels. The British fore was heavily battered, but left with enough guns to force the Dutch light line out of the fight. As the Dutch ships had come about, they had brought their guns across the fore and aft of the two British lines which forced the British light line out of the fight as well.

Dutch ships trying to reform into a more central position. The battle had already begun losing cohesion by this point in time.

The Achilles, leading the heavy British vessels was crossed by two thirds, which caused tremendous damage to the ship. Already pounded by the galleons, the Achilles took irreparable damage under the water line, forcing it out of the fight. The Mars, a British fourth directly behind her stopped to bring Leake aboard to continue the fight, but it was soon leapt upon by Dutch galleons and also surrendered.

The Achilles, leading the heavy British vessels was crossed by two thirds, which caused tremendous damage to the ship. Already pounded by the galleons, the Achilles took irreparable damage under the water line, forcing it out of the fight. The Mars, a British fourth directly behind her stopped to bring Leake aboard to continue the fight, but it was soon leapt upon by Dutch galleons and also surrendered.

The Achilles was hit hard by Dutch fire from both their 60 gun galleons and from a 72 gun third rate.

The British reacted by swarming the galleons with smaller ships, but despite superior positioning, the lighter, fewer guns were making only very limited impressions on the tough Dutch ships. The Dutch, still sparring with the heavier British frigates and ships of the line were forced into a more general brawl. Curen had lost his nerve after finding himself surrounded by the British fleet and out of position, leaving the Dutch similarly without command. When his crew detected a hull breach, they struck their colours, hoping to fix the damage while the remainder of their fleet won the battle. They would manage to patch their hull before she was sunk, but Curen, like Leake, was out of action.

The British reacted by swarming the galleons with smaller ships, but despite superior positioning, the lighter, fewer guns were making only very limited impressions on the tough Dutch ships. The Dutch, still sparring with the heavier British frigates and ships of the line were forced into a more general brawl. Curen had lost his nerve after finding himself surrounded by the British fleet and out of position, leaving the Dutch similarly without command. When his crew detected a hull breach, they struck their colours, hoping to fix the damage while the remainder of their fleet won the battle. They would manage to patch their hull before she was sunk, but Curen, like Leake, was out of action. The Dutch were at a clear advantage once their ships managed to get back into the midst of the general pell-mell of combat. The remaining vessels were two third rates, two galleons, and two fifth rates, though the Spartiate was down to eighteen guns, and one of their galleons caught fire temporarily pushing them out of the fight. The British had a sloop, a trio of fifth rates, and a heavily battered fourth rate, as well as several captured trade Indiamen that they had taken as prizes.

The Dutch were at a clear advantage once their ships managed to get back into the midst of the general pell-mell of combat. The remaining vessels were two third rates, two galleons, and two fifth rates, though the Spartiate was down to eighteen guns, and one of their galleons caught fire temporarily pushing them out of the fight. The British had a sloop, a trio of fifth rates, and a heavily battered fourth rate, as well as several captured trade Indiamen that they had taken as prizes.

The general chaos of a close quarters disorganized battle. A Dutch galleon is alight in the midst of it all, their crew desperately trying to douse the flames.

The fight continued on for a short while, ships careful to avoid destroying surrendered vessels so as to facilitate capture. Weaving in and around the dozens of stationary, inactive vessels, the few ships who had yet to surrender hunted between the hulks of their former enemies and allies. The most conspicuous mark were filled sails which guided the hunters and the hunted through the melee.

The fight continued on for a short while, ships careful to avoid destroying surrendered vessels so as to facilitate capture. Weaving in and around the dozens of stationary, inactive vessels, the few ships who had yet to surrender hunted between the hulks of their former enemies and allies. The most conspicuous mark were filled sails which guided the hunters and the hunted through the melee.

The fight quickly degenerates. Only a handful of ships were still active in the crowded warzone, yet the ocean felt crowded with ships. Ships that were near to sinking surrendered rather than trying to flee, as the white of sails were a beacon to cannon fire.

While the British had speed and manoeuvrability as they harried the massive Dutch ships through the dense pseudo terrain of the battle, the Dutch ships forced a ship out of the fight with near every volley. By days end, the entire British fleet had been sunk or captured.

While the British had speed and manoeuvrability as they harried the massive Dutch ships through the dense pseudo terrain of the battle, the Dutch ships forced a ship out of the fight with near every volley. By days end, the entire British fleet had been sunk or captured. The battle had been a bloody one. The Mars, along with Leake were captured by the Dutch, Leake sent to Amsterdam as a prisoner of war. The British fourth rate, the Agamemnon was also captured, but every other vessel was sunk or had exploded over the course of the battle. The British prize Indiamen, which had essentially failed to contribute to the battle were also run down and captured by the Dutch. The Dutch had lost two fifth rates, a fluyt and a bomb ketch, and most of the guns and crew of all of their remaining ships. The death count was estimated at approximately two thousand British, and over a thousand Dutch. Many of the British were drowned at sea, while many of the Dutch had been killed by consequence of direct cannon fire.

The battle had been a bloody one. The Mars, along with Leake were captured by the Dutch, Leake sent to Amsterdam as a prisoner of war. The British fourth rate, the Agamemnon was also captured, but every other vessel was sunk or had exploded over the course of the battle. The British prize Indiamen, which had essentially failed to contribute to the battle were also run down and captured by the Dutch. The Dutch had lost two fifth rates, a fluyt and a bomb ketch, and most of the guns and crew of all of their remaining ships. The death count was estimated at approximately two thousand British, and over a thousand Dutch. Many of the British were drowned at sea, while many of the Dutch had been killed by consequence of direct cannon fire.

The Achilles sinking to a watery grave. Many of the men of her crew would not survive the battle, and many men of sunken ships were unable to hold out until the end of the battle.

While the battle was a rousing success, Curen won little fame and glory from it. While his strategy had been sound, his own conduct during the battle was considered highly controversial. Historians debate whether or not his surrender during the battle was justified, or if he had truly had a breach which required repair. Most point to his experience aboard the Ter Goes holding his nerve under the sort of fire that other men would find overwhelming, but others note that he was not in a position of command in that battle. The general consensus is, he could have continued to fight the battle even if he had a breach in his hull. Damage was largely superficial when it arrived in port for repairs, and the breach which was taking in water could have been repaired without abandoning the guns or the fight. This conduct marred what would have otherwise been a glorious and heroic victory over the legendary British navy.

While the battle was a rousing success, Curen won little fame and glory from it. While his strategy had been sound, his own conduct during the battle was considered highly controversial. Historians debate whether or not his surrender during the battle was justified, or if he had truly had a breach which required repair. Most point to his experience aboard the Ter Goes holding his nerve under the sort of fire that other men would find overwhelming, but others note that he was not in a position of command in that battle. The general consensus is, he could have continued to fight the battle even if he had a breach in his hull. Damage was largely superficial when it arrived in port for repairs, and the breach which was taking in water could have been repaired without abandoning the guns or the fight. This conduct marred what would have otherwise been a glorious and heroic victory over the legendary British navy. Leake on the other hand was sent to Den Hague, as he had family there. While under guard in the United Provinces, he was treated fairly well, and was able to remain at his cousin’s estate during the remainder of the war. Back in Britain, he was marked a failure ruining the future prospects of a career, but with so much of the war remaining, John Leake would die comfortably with family in a summer cottage near Rotterdam.

Leake on the other hand was sent to Den Hague, as he had family there. While under guard in the United Provinces, he was treated fairly well, and was able to remain at his cousin’s estate during the remainder of the war. Back in Britain, he was marked a failure ruining the future prospects of a career, but with so much of the war remaining, John Leake would die comfortably with family in a summer cottage near Rotterdam.

John Leake retired to the Dutch countryside, even though he was technically a prisoner of war. Britain refused to pay to have him returned, and the Dutch didn't find it necessary to restrain or execute him. He lived a more prosperous life than the then controversial Curen.

Next Professor Douglas will be discussing the history of roads and the effect they had on society. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.

Next Professor Douglas will be discussing the history of roads and the effect they had on society. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.