Part 25: January 16 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, Lewis Culling will be doing live coverage of a hundred and fifty year old Florentine parade. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twenty-fifth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed the famed naval battle of Hispaniola.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twenty-fifth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed the famed naval battle of Hispaniola. And with that battle, the Dutch could freely move their armies across the Atlantic as soon as the British were pushed away from the American theater, and once again, the European continental forces were in desperate need of armies. The Polish armies still menacing the Dutch from across their borders, split away from their Prussian allies, the Dutch could not react freely when in 1746 the Italian states, Genoa and Venice finally declared war on the Dutch.

And with that battle, the Dutch could freely move their armies across the Atlantic as soon as the British were pushed away from the American theater, and once again, the European continental forces were in desperate need of armies. The Polish armies still menacing the Dutch from across their borders, split away from their Prussian allies, the Dutch could not react freely when in 1746 the Italian states, Genoa and Venice finally declared war on the Dutch.

The Dutch had cleared the way from America to Europe.

With trade shut down across the Mediterranean by their raids, the Dutch were no longer earning enough money to easily pay them off as they had in past years. By drawing their Mediterranean fleet away to fight in the Americas, the Dutch left themselves with a critical opening which was quickly exploited. The armies of the Dutch, returning from India and landing in North Africa were redirected to the Italian peninsula.

With trade shut down across the Mediterranean by their raids, the Dutch were no longer earning enough money to easily pay them off as they had in past years. By drawing their Mediterranean fleet away to fight in the Americas, the Dutch left themselves with a critical opening which was quickly exploited. The armies of the Dutch, returning from India and landing in North Africa were redirected to the Italian peninsula.

Venice, a city of canals. The city is mostly built over water, and as such waterways and boats take the place of roads.

The Italians couldn’t have chosen a more awkward time in the end. While they had managed to severely disrupt Dutch trade and the V.O.C.’s economy, they had relied on a Dutch inability to move forces south from Munich and Austria to deal with the tiny peninsula. They were, in a sense correct, as the Dutch were incapable of moving many of their forces away from the Polish. However, by redirecting the V.O.C.’s forces, which refused to allow the trade ports receiving their goods remain under blockade, the Italians were suddenly outnumbered along multiple fronts.

The Italians couldn’t have chosen a more awkward time in the end. While they had managed to severely disrupt Dutch trade and the V.O.C.’s economy, they had relied on a Dutch inability to move forces south from Munich and Austria to deal with the tiny peninsula. They were, in a sense correct, as the Dutch were incapable of moving many of their forces away from the Polish. However, by redirecting the V.O.C.’s forces, which refused to allow the trade ports receiving their goods remain under blockade, the Italians were suddenly outnumbered along multiple fronts.

The Italians had thought they were in a strong position, as they were unaware of the approaching V.O.C. ships and armies.

During the 1700s, Italy was not a unified nation. Most cities were their own sovereign and independent state. This meant the disorganized city states had to collaborate to fight larger political entities. This meant the panic of a mob, or the general outrage of the masses was amplified, a major contributing factor to their reckless entry into the war against the Dutch. Venice on the other hand, was a moderately large region which was comparatively unified. They had been declining on both power and influence for over a hundred years, and their merchant navy had been reduced to a fraction of their former power after decades of war with the Ottomans. The larger threat of the 1700s however, was the encroachment of the Dutch merchant navies across the Mediterranean. With a near world monopoly, and trade income reaching the hundreds of millions to their enemies, the Ottomans, the citizens of Venice were increasingly prone to blaming the Dutch for their economic troubles. The discontent led them to sign an alliance with the Italian states to go to war with the Dutch.

During the 1700s, Italy was not a unified nation. Most cities were their own sovereign and independent state. This meant the disorganized city states had to collaborate to fight larger political entities. This meant the panic of a mob, or the general outrage of the masses was amplified, a major contributing factor to their reckless entry into the war against the Dutch. Venice on the other hand, was a moderately large region which was comparatively unified. They had been declining on both power and influence for over a hundred years, and their merchant navy had been reduced to a fraction of their former power after decades of war with the Ottomans. The larger threat of the 1700s however, was the encroachment of the Dutch merchant navies across the Mediterranean. With a near world monopoly, and trade income reaching the hundreds of millions to their enemies, the Ottomans, the citizens of Venice were increasingly prone to blaming the Dutch for their economic troubles. The discontent led them to sign an alliance with the Italian states to go to war with the Dutch.

Italy, despite being about the size of one of the countries within Britain was broken into many small sovereign states, some only as large as a city. This meant Italy could not organize a unified defense as easily as other nations.

Genoa, another comparatively powerful Italian city state controlling a large region was one of the linchpin deciding factors in the conduct of the war. Venice and the other Italian states could not invade the Dutch without their help, as they were the only ones in a position to successfully invade through Milan, then across the mountains into the Dutch heartlands. They had been paid a tremendous sum to join the alliance.

Genoa, another comparatively powerful Italian city state controlling a large region was one of the linchpin deciding factors in the conduct of the war. Venice and the other Italian states could not invade the Dutch without their help, as they were the only ones in a position to successfully invade through Milan, then across the mountains into the Dutch heartlands. They had been paid a tremendous sum to join the alliance.

The Genoese were famous for their crossbowmen, such as these mercenaries that fought at Crecy. They hadn't advanced as much as other nations since the 1700s, and as such were not as formidable as they had once been.

Unfortunately for their alliance the various states each wanted to preserve their own armies, letting their allies take the brunt of the Dutch assault. This meant the Dutch could take apart each of their states one by one. The Italian states were the first invaded, the V.O.C. forces from the Indian sub-continent who had stopped over in North Africa while returning home landing near the Vatican a year after. Unwilling to incite the entire Catholic populace within their Empire, the Dutch opted for a surrender under supposedly amicable terms, gaining millions in reparations under the terms of peace.

Unfortunately for their alliance the various states each wanted to preserve their own armies, letting their allies take the brunt of the Dutch assault. This meant the Dutch could take apart each of their states one by one. The Italian states were the first invaded, the V.O.C. forces from the Indian sub-continent who had stopped over in North Africa while returning home landing near the Vatican a year after. Unwilling to incite the entire Catholic populace within their Empire, the Dutch opted for a surrender under supposedly amicable terms, gaining millions in reparations under the terms of peace.

Vatican city. The Dutch were unwilling to sack and occupy one of the holiest cities in Christianity even though the Dutch government itself was Protestant. Representatives of the Vatican were able to negotiate peace with the Dutch under the terms that all other Italian states pay reparations.

Venice was not so lucky. While a comparatively minor trade nation, they had been a consistent competitor, and the Dutch were more than willing to wipe their trade from the seas, and to take their wealthy port cities. The Dutch managed to move portions of their army from Munich, Austria and Croatia into a consolidated force, hoping they could put together a full army without over-diluting their front line against Poland. This army marched on Venice, and destroyed the defenses without much pause. The forces of Venice were far smaller than the forces that Austria had making the battle fairly catastrophic for them.

Venice was not so lucky. While a comparatively minor trade nation, they had been a consistent competitor, and the Dutch were more than willing to wipe their trade from the seas, and to take their wealthy port cities. The Dutch managed to move portions of their army from Munich, Austria and Croatia into a consolidated force, hoping they could put together a full army without over-diluting their front line against Poland. This army marched on Venice, and destroyed the defenses without much pause. The forces of Venice were far smaller than the forces that Austria had making the battle fairly catastrophic for them.

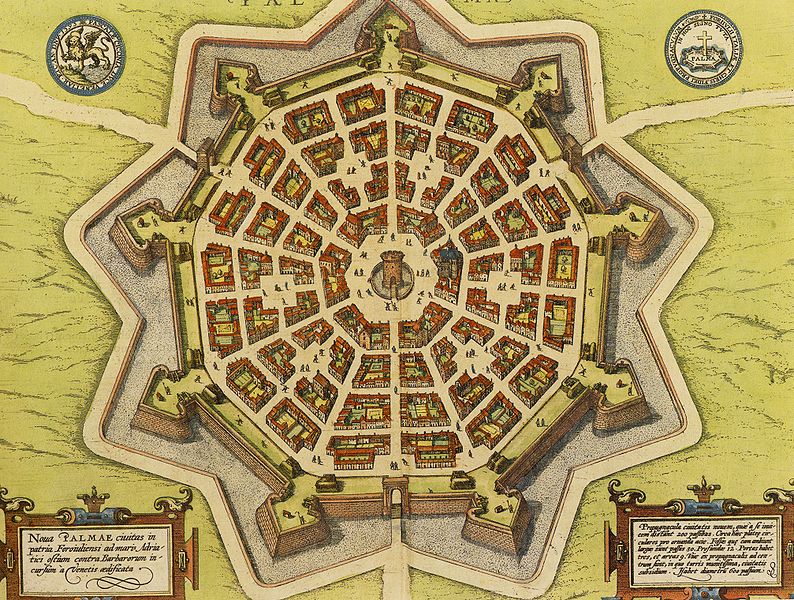

The Italians were masters of star forts, which were likely invented in Italy in response to wars with France. The fortress was far more difficult to take even when cannons had cleared portions of their walls.

The Venetians had split their forces, assuming their fortifications would allow them to hold their capital. Chioggia, their key trade port held a large portion of their forces, as the port was their entire state’s lifeline to both their economy and to the food required to feed their populace. This meant the siege of Venice consisted of mostly poor quality armed peasantry and factory workers defending against the veterans from Amsterdam of the conquest of Germany and Austria.

The Venetians had split their forces, assuming their fortifications would allow them to hold their capital. Chioggia, their key trade port held a large portion of their forces, as the port was their entire state’s lifeline to both their economy and to the food required to feed their populace. This meant the siege of Venice consisted of mostly poor quality armed peasantry and factory workers defending against the veterans from Amsterdam of the conquest of Germany and Austria.

The Dutch assault the city of Venice. The Italian defenders were spread across their territory where they should have been focused in the city of Venice.

The Dutch, unlike in many of their other siege offenses enjoyed a tremendous advantage in melee combat, and therefore opted to surround the walls of Venice and assault them directly rather than destroying them through sustained artillery fire. While the Dutch did breach the walls of Venice, and they did scour them with artillery fire to clear defenders as they moved forward, the majority of the combat was conducted by the infantry.

The Dutch, unlike in many of their other siege offenses enjoyed a tremendous advantage in melee combat, and therefore opted to surround the walls of Venice and assault them directly rather than destroying them through sustained artillery fire. While the Dutch did breach the walls of Venice, and they did scour them with artillery fire to clear defenders as they moved forward, the majority of the combat was conducted by the infantry.

Though the assault of Venice was famous for the brave and otherwise suicidal infantry assault, artillery still took a tremendous toll on the Dutch forces.

This army had been formed mostly from the top elite soldiers of the Dutch army, that being their grenadiers, Swiss mercenaries and Scottish mercenaries. Unlike the standard Dutch army which could not necessarily force their way through an enemy wall and choke point in a fortification, these members had the skills necessary to force their way onto the walls.

This army had been formed mostly from the top elite soldiers of the Dutch army, that being their grenadiers, Swiss mercenaries and Scottish mercenaries. Unlike the standard Dutch army which could not necessarily force their way through an enemy wall and choke point in a fortification, these members had the skills necessary to force their way onto the walls.

Dutch Grenadiers, easily identified by their caps. The Grenadiers were powerful on the charge and in melee, probably because only the tallest, strongest men could become grenadiers.

The Dutch obviously would have preferred a long term siege, but while the day had started clear and sunny, the battle shortly after fell under a terrible storm ruining fuses, dampening the quicklime clouds and causing artillery misfires. Having committed to a timeline by then, the Dutch continued the assault when it became clear the rain would not clear before new powder could be brought up from Austria, and they wished to fight before the moisture ruined their stores.

The Dutch obviously would have preferred a long term siege, but while the day had started clear and sunny, the battle shortly after fell under a terrible storm ruining fuses, dampening the quicklime clouds and causing artillery misfires. Having committed to a timeline by then, the Dutch continued the assault when it became clear the rain would not clear before new powder could be brought up from Austria, and they wished to fight before the moisture ruined their stores.

Rain breaks out after the Dutch deploy, fouling the cannons and ruining unprotected powder charges. Artillery engineers wait for wax sealed charges to be brought forward along with wooden covers.

Once the Dutch had cleared the walls, they managed to pour fire into the exposed courtyard, giving the grenadiers time and space to move to the center to bombard their final defenses with their grenades. These short fused, heavy, hand lit bombs were sometimes as much a danger to their thrower as their target, but when a battalion took a volley of grenades, it would often completely shatter their morale. While the few remaining defenders were completely disoriented by the Dutch grenades, the grenadiers charged in to clear them away.

Once the Dutch had cleared the walls, they managed to pour fire into the exposed courtyard, giving the grenadiers time and space to move to the center to bombard their final defenses with their grenades. These short fused, heavy, hand lit bombs were sometimes as much a danger to their thrower as their target, but when a battalion took a volley of grenades, it would often completely shatter their morale. While the few remaining defenders were completely disoriented by the Dutch grenades, the grenadiers charged in to clear them away.

Grenadiers bomb the defenders holding the fort's center. After throwing their bombs and firing their loaded guns, the grenadiers finished off the last few with a bayonet charge.

This did not knock the Venetians out of the war however. Their forces had spread to the Middle East prior to the war, and their main force in Venice itself had remained in their port city hoping to deny it to the Dutch. Defending their navy of trade ships and brigs, they hoped to deny the Dutch the lucrative trade port as long as they could manage under the assumption the Italian states would resume their attack against the Dutch, or that Genoa could reverse the Dutch offensive from the west.

This did not knock the Venetians out of the war however. Their forces had spread to the Middle East prior to the war, and their main force in Venice itself had remained in their port city hoping to deny it to the Dutch. Defending their navy of trade ships and brigs, they hoped to deny the Dutch the lucrative trade port as long as they could manage under the assumption the Italian states would resume their attack against the Dutch, or that Genoa could reverse the Dutch offensive from the west.

The force of Venice were holding out in their trade port at Chioggia

That assumption was based on old information however. While the Dutch in Milan were indeed outmatched by Genoese forces, the second wave of troops returning from India arrived shortly after the first and were deployed in Genoa. The troops withdrawn from Rome after the Italian states surrendered were also quickly redeployed to Genoa held Corsica, tying down their remaining forces. The final nail in the coffin for the Genoese was the large V.O.C. fleet returning from India and moving to counter the weak Genoese fleet.

That assumption was based on old information however. While the Dutch in Milan were indeed outmatched by Genoese forces, the second wave of troops returning from India arrived shortly after the first and were deployed in Genoa. The troops withdrawn from Rome after the Italian states surrendered were also quickly redeployed to Genoa held Corsica, tying down their remaining forces. The final nail in the coffin for the Genoese was the large V.O.C. fleet returning from India and moving to counter the weak Genoese fleet.

Corsica. An idyllic yet poor island was a land that moved between the hands of many conquerors through their bloody history.

The Genoese fleet, much like the other Italian states could not draw the resources together to create powerful ships of the line as the Dutch did. Without many wealthy taxable provinces, or a massive worldwide trade network, states such as them could only afford smaller sloops or brigs. Brigs were the more powerful choice, but they had a minor flaw. Their powder hold was far larger than a sloops, as the ship itself was smaller, yet the powder hold was larger to accommodate the larger number of guns. This meant that more hits against a brig hit the powder hold. They also had thin hulls, all of which was a recipe for an explosion when forced into a fight against a ship with larger cannons.

The Genoese fleet, much like the other Italian states could not draw the resources together to create powerful ships of the line as the Dutch did. Without many wealthy taxable provinces, or a massive worldwide trade network, states such as them could only afford smaller sloops or brigs. Brigs were the more powerful choice, but they had a minor flaw. Their powder hold was far larger than a sloops, as the ship itself was smaller, yet the powder hold was larger to accommodate the larger number of guns. This meant that more hits against a brig hit the powder hold. They also had thin hulls, all of which was a recipe for an explosion when forced into a fight against a ship with larger cannons.

The Dutch move their fleet against the Genoese. The fog and limitations to viewing made it difficult for either side to properly gauge the strength of individual enemy ships, meaning the Genoese went to battle assuming the Dutch were attacking with their Mediterranean brigs and sloops with only a pair of frigates, and did not know of the frigates from India reinforcing them.

The Dutch fleet in the Mediterranean was a series of fifth rate ships supported by a small number of sloops and brigs as well. Their proper ships of the line were too busy policing both the Americas and watching the channel, and so the heaviest ships in the Mediterranean were those frigates. Even so the Spartiate had demonstrated the power gap between a flotilla of brigs and a single frigate.

The Dutch fleet in the Mediterranean was a series of fifth rate ships supported by a small number of sloops and brigs as well. Their proper ships of the line were too busy policing both the Americas and watching the channel, and so the heaviest ships in the Mediterranean were those frigates. Even so the Spartiate had demonstrated the power gap between a flotilla of brigs and a single frigate. This battle had been conducted with fairly little strategy. The Genoese ships, their backs to the shore could not retreat from the Dutch ships, and were forced into a general slugging match. The Dutch ships were formed into two sections, their frigates and their supporting ships. The main line of Dutch ships manoeuvred to get directly into the midst of the Genoese to guarantee the maximum amount of chaos among them while the lighter ships moved around the outskirts to fire from a safer distance.

This battle had been conducted with fairly little strategy. The Genoese ships, their backs to the shore could not retreat from the Dutch ships, and were forced into a general slugging match. The Dutch ships were formed into two sections, their frigates and their supporting ships. The main line of Dutch ships manoeuvred to get directly into the midst of the Genoese to guarantee the maximum amount of chaos among them while the lighter ships moved around the outskirts to fire from a safer distance.

The Italian and Dutch ships simply collide immediately into a close range pell mell.

After the initial clash, the weakness of Brigs had already shown their face with their lead ship and their admiral going up in a massive explosion, killing the entire crew immediately. The ensuing chaos and panic caused the entire Genoese line to get into a gridlocked formation with the Dutch where every ship fired straight point blank into every ship nearby without any regard to movement or tactics.

After the initial clash, the weakness of Brigs had already shown their face with their lead ship and their admiral going up in a massive explosion, killing the entire crew immediately. The ensuing chaos and panic caused the entire Genoese line to get into a gridlocked formation with the Dutch where every ship fired straight point blank into every ship nearby without any regard to movement or tactics.

The battle had barely been initiated when the first Genoese ship is blown apart. The death of their Admiral in such a terrible death left the remaining Genoese fleet in shambles.

A second Genoese brig was blown apart during the melee, and that explosion sparked the complete surrender of the remaining fleet. While suitable for an engagement against a similar fleet, or a galley fleet in the Mediterranean, those vessels were definitely incapable of engaging stronger vessels.

A second Genoese brig was blown apart during the melee, and that explosion sparked the complete surrender of the remaining fleet. While suitable for an engagement against a similar fleet, or a galley fleet in the Mediterranean, those vessels were definitely incapable of engaging stronger vessels.

A second explosion. The Genoese were completely demoralized, and promptly surrendered.

Without their fleet, the Dutch were able to completely besiege and cover the entire kingdom of Genoa. The Dutch had opted to wait out the siege in both Corsica and Genoa, as the armies had been demoralized and exhausted by the lengthy journey through cargo ships all the way from India and were less willing to fight. The Genoans, much like the Venetians in Chioggia were hoping their allies would help defeat the Dutch and lift the siege.

Without their fleet, the Dutch were able to completely besiege and cover the entire kingdom of Genoa. The Dutch had opted to wait out the siege in both Corsica and Genoa, as the armies had been demoralized and exhausted by the lengthy journey through cargo ships all the way from India and were less willing to fight. The Genoans, much like the Venetians in Chioggia were hoping their allies would help defeat the Dutch and lift the siege. The fleet of Venice in Chioggia was much the same as the Genoese one, and the Dutch fleet without even stopping to repair after their very recent battle moved directly to assault them, confident that there would be a repeat of the previous battle. The army stationed in Venice forced the forces of Venice to retreat to the sea where the Dutch navy was waiting.

The fleet of Venice in Chioggia was much the same as the Genoese one, and the Dutch fleet without even stopping to repair after their very recent battle moved directly to assault them, confident that there would be a repeat of the previous battle. The army stationed in Venice forced the forces of Venice to retreat to the sea where the Dutch navy was waiting.

The Dutch move their fleet around to blockade and engage the Venetian fleet.

And this battle was much like their one only a few months prior. The Dutch deployed in two wings, their heavy ships on their left, the support ships on the right. The Venetians were well informed of the battle to the West of Italy and managed to spread their ships apart to prevent the ships from going from point blank range without room to maneuver. However, the Dutch were still able to blow the brigs out of the water. While a more difficult battle in that sense, however the Venetian ships had been badly damaged in their escape from port in their rush to avoid capture from the Dutch army letting the Dutch run them down very easily.

And this battle was much like their one only a few months prior. The Dutch deployed in two wings, their heavy ships on their left, the support ships on the right. The Venetians were well informed of the battle to the West of Italy and managed to spread their ships apart to prevent the ships from going from point blank range without room to maneuver. However, the Dutch were still able to blow the brigs out of the water. While a more difficult battle in that sense, however the Venetian ships had been badly damaged in their escape from port in their rush to avoid capture from the Dutch army letting the Dutch run them down very easily.

The Venetians managed to keep their forces less clumped than the Genoese had, but their superior maneuverability wasn't enough to defeat the Dutch frigates.

Their army however, had managed a retreat back into the Alps hoping to get away from the main line of conflict. They were met by the army stationed in Munich which had managed to maneuver against them by winter. The tired Italian army was mostly cavalry, matched against a mostly infantry based Dutch force. Lacking the required stores to keep their horses fed, and to survive the winter without reaching the Dutch supply lines, they were unable to turn back, as the Dutch would simply hedge them between their Munich force and their force stationed in Venice.

Their army however, had managed a retreat back into the Alps hoping to get away from the main line of conflict. They were met by the army stationed in Munich which had managed to maneuver against them by winter. The tired Italian army was mostly cavalry, matched against a mostly infantry based Dutch force. Lacking the required stores to keep their horses fed, and to survive the winter without reaching the Dutch supply lines, they were unable to turn back, as the Dutch would simply hedge them between their Munich force and their force stationed in Venice.

The Munich forces catch the Venetian forces that were attempting to retreat into the alps to hide. Finding themselves out of the frying pan and in the fire, the Italians attempt a breakthrough before they can be surrounded by the Dutch in Venice.

The Dutch deployed in line to stop a breakthrough, their skirmishers pounding anti-cavalry stakes into the ground to stop a cavalry charge. The impetuous Italian cavalry were running forward at an unfortunate time, but at the same time, the Dutch riflemen were forced to return fire without moving into their staggered formation to avoid friendly fire. Dozens of them were killed by friendly fire before they could move into the proper position, but the Italian cavalry charge was almost entirely mown down.

The Dutch deployed in line to stop a breakthrough, their skirmishers pounding anti-cavalry stakes into the ground to stop a cavalry charge. The impetuous Italian cavalry were running forward at an unfortunate time, but at the same time, the Dutch riflemen were forced to return fire without moving into their staggered formation to avoid friendly fire. Dozens of them were killed by friendly fire before they could move into the proper position, but the Italian cavalry charge was almost entirely mown down.

The Skirmishers barely prepare themselves against the Italian charge. Caught on their back heel due to the rapid charge of the cavalry, the Dutch find themselves out of position and suffering friendly fire.

A second squad of cavalry tried to move around the flank to spike the Dutch howitzers forcing two Dutch line infantry out of line to block, one of which was forced into squares. Repulsed on the Dutch right flank, as well as in their center, the Venetians moved their line into a strong position to counter the Dutch, anchoring their left with their foot artillery masked by some of their remaining cavalry. Their line was only a third the strength of the Dutch line, and without an advantage in artillery, it was clear by then that they would lose.

A second squad of cavalry tried to move around the flank to spike the Dutch howitzers forcing two Dutch line infantry out of line to block, one of which was forced into squares. Repulsed on the Dutch right flank, as well as in their center, the Venetians moved their line into a strong position to counter the Dutch, anchoring their left with their foot artillery masked by some of their remaining cavalry. Their line was only a third the strength of the Dutch line, and without an advantage in artillery, it was clear by then that they would lose.

After defeating the initial shock charge by the Italians, the Dutch were in a strong position to clear out the remainder of the Venetians, their line consisting of far more infantry than the Italian one.

The Dutch army, hoping to reduce casualties to their army sent some of their cavalry forward to spike the foot artillery, but were countered by the Venetian cavalry. The forward infantry that had blocked for the Dutch artillery charged forward to assist.

The Dutch army, hoping to reduce casualties to their army sent some of their cavalry forward to spike the foot artillery, but were countered by the Venetian cavalry. The forward infantry that had blocked for the Dutch artillery charged forward to assist.

The Dutch see an opportunity to take out exposed cannons, but are shortly chased away by Italian cavalry.

The rest of the Dutch line began firing at the Venetian line opening with their long range rifles, forcing the Italian line into engaging the Dutch directly rather than moving around their flank to assist their outnumbered cavalry. The Dutch line behind their skirmishers quickly moved up to replace their lighter infantry while others moved around to flank.

The rest of the Dutch line began firing at the Venetian line opening with their long range rifles, forcing the Italian line into engaging the Dutch directly rather than moving around their flank to assist their outnumbered cavalry. The Dutch line behind their skirmishers quickly moved up to replace their lighter infantry while others moved around to flank.

The Dutch light infantry were causing dozens of casualties to the Italians before the Italians could return fire, forcing them forward.

Advancing into the teeth of the Dutch light infantry fire, then directly into the line infantry fire which were flanking them quickly forced the remaining Venetian army to flee. With these forces defeated, the Italian campaign was nearly completed, save for the cleanup of the Genoan forces.

Advancing into the teeth of the Dutch light infantry fire, then directly into the line infantry fire which were flanking them quickly forced the remaining Venetian army to flee. With these forces defeated, the Italian campaign was nearly completed, save for the cleanup of the Genoan forces.

The Dutch surrounding the small line of Venetians.

Next we will have a special live coverage of a traditional parade in Florence. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.

Next we will have a special live coverage of a traditional parade in Florence. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.